Ore and order: Russia’s rare-earth strategy for the Ukraine talks

In May 2025, when US and Ukraine discussed the “minerals-for-aid” deal, Moscow pointed out the obvious: Russia’s rare-earth reserves dwarf Ukraine’s. By December, elements of that argument had crept into US president Donald Trump’s peace plan, which included major American investments in Russia’s rare-earth and energy sectors. With Europe signalling a possible thaw in talks with Russia—Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni recently joined French president Emmanuel Macron’s call to reopen diplomacy with Vladimir Putin—Moscow smells an opening to press the same leverage.

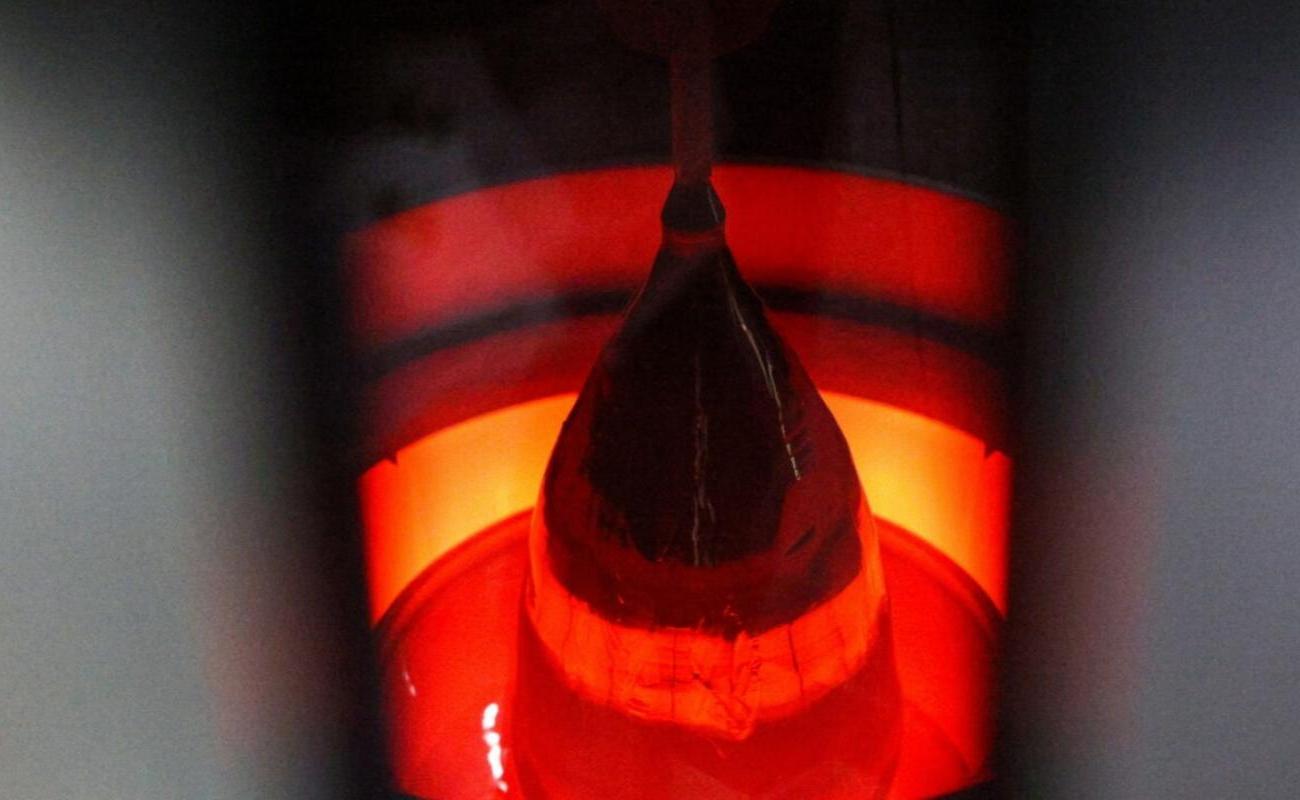

At the heart of the strategy is Russia’s Angara–Yenisei Valley, a planned $9.2bn Siberian processing hub overseen by Sergei Shoigu, the secretary of the Russian Security Council, former minister of defence and a figure close to Putin. With this project, Russia hopes to raise its global supply share of rare earths from 1.3% today to 10% by 2030.

Russia reads calls to revive diplomatic engagement as evidence that European economic pragmatism is resurfacing. Europe’s appetite for rare earths gives Russia’s mineral diplomacy a wedge and is likely to test the bloc’s cohesion.

China’s chokehold

Russian officials know that the West’s overreliance on Chinese rare earths is a strategic weakness. China controls about 60% of the world’s rare-earth mining and nearly 90% of refining. Its grip of the sector is also about regulation and information: export licences now forces Western companies to disclose client lists, stock levels and production forecasts. Beijing therefore knows which factories would shut down after a week without its supplies and which firms have no fallback options. In 2023, China has placed 12 of 17 rare-earth elements under export control; in November 2025, it temporarily suspended the export of five. Shipments now require a licence that can be delayed or denied.

Meanwhile, EU imports of rare earths climbed from around 11,000 to 18,000 between 2019 and 2022. Every high-tech industry now runs on rare earths. Each electric car carries up to two kilograms of them in its magnets and catalysts. Rare earths also power wind turbines, robotics, precision manufacturing and modern defence systems. If Beijing decides to restrict the export of these materials, their trillion-dollar ecosystem could collapse. In 2024, when the Chinese export licences were being rolled out, EU imports of rare earths fell by 29% in a single year.

When Europe does not buy from China, it already turns to Russia. Estonia, which hosts Europe’s biggest rare-earth processing plant (in Narva, right at the Russian border), imports 88% of its rare earths from Russia. According to the head of another rare-earth plant in the country, “if Russia’s rare-earth supply is interrupted, we will not have a Western European defence industry.” The plant’s location at the Russian border symbolises Europe’s predicament: proximity offers logistical and economic convenience, but it also exposes it to Russian coercion.

Siberian alternative

The fact that Moscow has put Shoigu in charge and named first deputy prime minister Denis Manturov to chair its board signals the political weight of the project.

Russia is betting big on the Angara-Yenisei Valley project with the creation of a special economic zone, tax breaks and infrastructure support. At least eight companies will open processing plants of lithium-battery materials, germanium—a metal critical for microelectronics that Russia currently lacks—and aluminium powder used in 3D printing, among others. Utilities and transport are expected to be in place by mid-2026, with the first companies due online by 2028.

The fact that Moscow has put Shoigu in charge and named first deputy prime minister Denis Manturov to chair its board signals the political weight of the project. Shoigu has long promoted Siberia as the centre of Russian development (he used to organise fishing trips for Putin in the taiga). It also shows his resilience in the Russian political system after his somewhat problematic departure from the Ministry of Defence. Meanwhile, Manturov is the main Russian government official running industrial policy, including in the military sector.

Reality check

Executing the Angara-Yenisei Valley plan depends as much on Russian capacity to build it as on the willingness of foreign actors to invest in it. Russia’s proven rare earth reserves—about 28.7m tons—rank among the world’s largest, but Russia lacks the latest technologies for extraction and processing. Chinese partners are reluctant to share them and Western sanctions complicate things further.

Currently, few European firms will invest in Russia without legal and financial cover from national governments. Russian officials appear to assume that Europe’s dependence on China, weak growth prospects and Trump’s confrontational posture toward the EU will eventually push European governments to provide such support. Some Europeans might indeed be tempted to sell economic deals with Moscow as a “European solution” to the war in Ukraine, or a bulwark against American pressure and Chinese export coercion.

European leaders will need to have a solid strategy in place if they want to resist that carrot, such as refusing to link economic engagement with conditions on Ukraine, as well as oppose the idea that trade with Moscow is a shortcut to autonomy. The sheer size of Angara-Yenisei Valley ensures that even an under-delivered outcome will satisfy powerful ministries, state firms and industrial elites, shoring up the stability of the Russian regime.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.