The Brief — Russian rift in Europe

The death of Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet leader who saw out the last days of the Cold War, helping to bring it to a peaceful close, has highlighted how some divisions in Europe are here to stay.

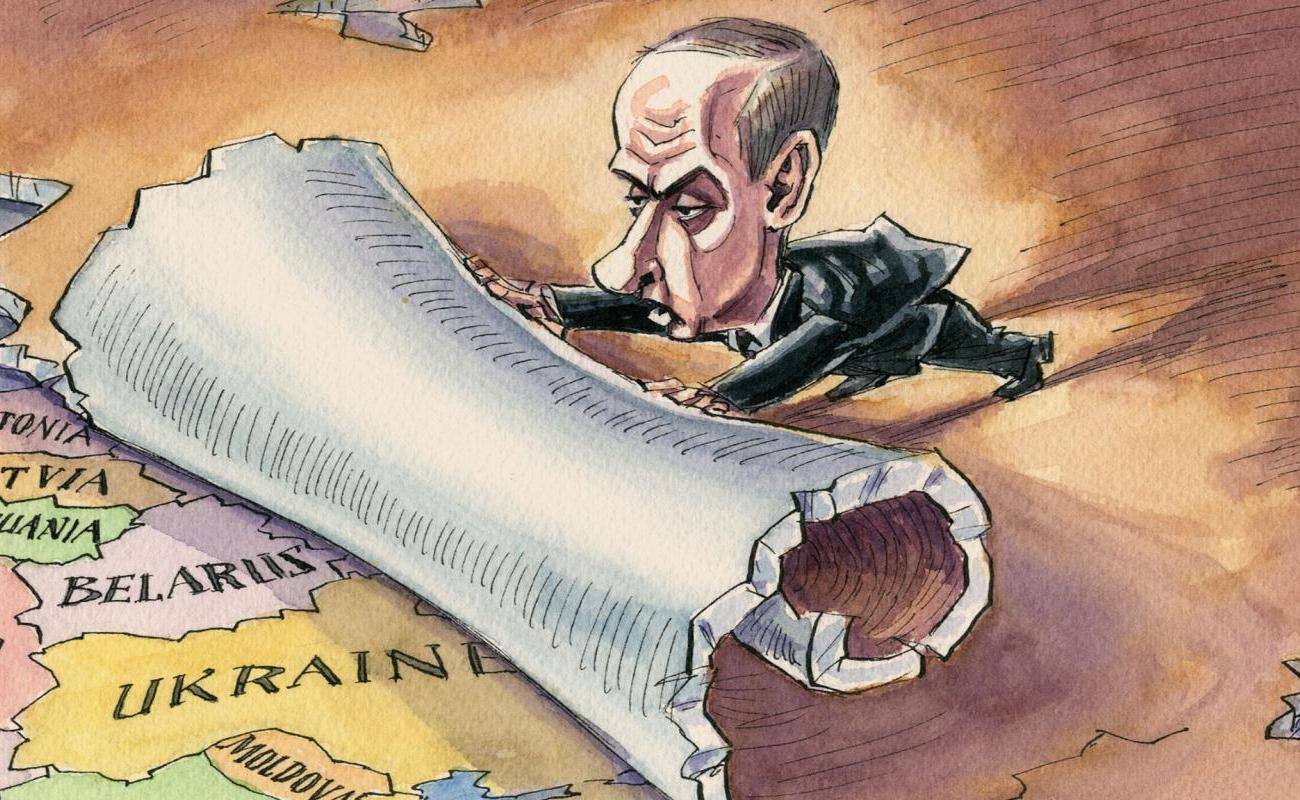

His political legacy of reforming and liberalising the Soviet economy and society was destroyed by Vladimir Putin, who replaced glasnost (openness), détente (the relaxation of strained relations) and arms control with expansionist superpower hubris.

Gorbachev’s well-documented love-hate relationship with Putin was a domestic rollercoaster, but it didn’t stop the ex-Soviet leader from supporting the current Russian president. Putin, in turn, had little to say of Gorbachev’s achievements in his bland condolence statement.

Russian citizens, old and young, largely share a disdain for Gorbachev, with the former associating him with tough times caused by the collapse of the command economy. The latter, raised under Putin, romanticise the Soviet past and blame Gorbachev for squandering away the communist empire.

In the West – and especially in Western Europe – political leaders rightfully remembered his role in bringing the Soviet Union closer to the West and dismantling the ‘Iron Curtain’.

But those who mourn Gorbachev as a peace champion (and a Nobel Peace Prize winner) would do well to remember that his death has not brought the same level of veneration across all of Europe, particularly in former Soviet countries.

When pro-democracy protests rocked communist Eastern Europe in 1989, Gorbachev refrained from using force, breaking with the legacy of previous Soviet leaders who did not hesitate to send tanks to crush uprisings in Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Still, the Soviet army did cause some bloodshed in its dying days, more or less under his watch.

“Lithuanians will not glorify Gorbachev. We will never forget the simple fact that his army murdered civilians to prolong his regime’s occupation of our country,” Lithuania’s Foreign Minister Gabrelius Landsbergis tweeted on Wednesday.

“His soldiers fired on our unarmed protestors and crushed them under his tanks. That is how we will remember him,” he wrote.

This is the darker side of his legacy: plunging living standards in the USSR, and military repression in the Baltics and Central Asia.

“When we hear today that he was a great leader and statesman, maybe he did not commit such serious crimes against the background of other, earlier leaders of the Soviet Union, but he is responsible, like all the creators of this criminal system,” Poland’s deputy foreign minister Paweł Jabłoński told Polskie Radio.

In some sense, the East-West divide in reactions to his death is a perfect analogy for how differently Russia was perceived by Western Europeans until this year (and still is by some), compared to the highly-strung Eastern Europe, always wary of its nemesis in Moscow.

This perception of two Russias does exist, although Poles, Balts and some of their Nordic and Central European neighbours have toned down their ‘we told you so’ rhetoric and EU unity has become the common political refrain.

EU foreign ministers are meeting informally in Prague this week to kick off discussions about the EU’s long-term approach towards Russia, which are likely to dominate Europe’s political fall season.

At the centre of the debate will be a revision of the EU’s five guiding principles for its relations with Moscow, which can be summed up as “push back, contain, and engage” – some of which have already become obsolete.

Some hawks might argue that Russia is not European and never will be.

Force remains a proven means with Moscow’s political elite and it is increasingly difficult to believe that the ‘silent majority’ of Russians don’t support Putin’s actions, they say.

More optimistic souls hope for a change of guard in the Kremlin and the chance of a fresh start after Putin. But for now, this remains wishful thinking.

Seven months into Russia’s war in Ukraine, Europe’s most urgent concern – and the chief focus of discussion – is how to keep its citizens warm and fed this winter, in the context of skyrocketing energy prices and destabilised food supply chains.

Without taking a sober look at Moscow, Europeans might never find an adequate strategy for dealing with Putin’s conservative, anti-Western approach to power.