Policy orientations on EU-China relations in semiconductors: an outlook on bilateral and multilateral agendas

The international agenda on semiconductors is not only a matter of US-China rivalry. Also, the EU plays a major role, in terms of economy, industrial policy and security. Moreover, jointly with EU institutions, each Member State needs to decide which approach to semiconductors, to China and to global technology governance it aims to undertake.

Semiconductors have been embedded through an economic security outlook. However, this area cannot be only addressed on a bilateral basis. The understanding of how the EU’s own technology partnerships with third countries are framed will provide policy guidance on how the Union may approach China, in their own mutual relationship and in how both sides reflect their own agendas within international fora and multilateral dialogues where semiconductors play an increasingly strategic role.

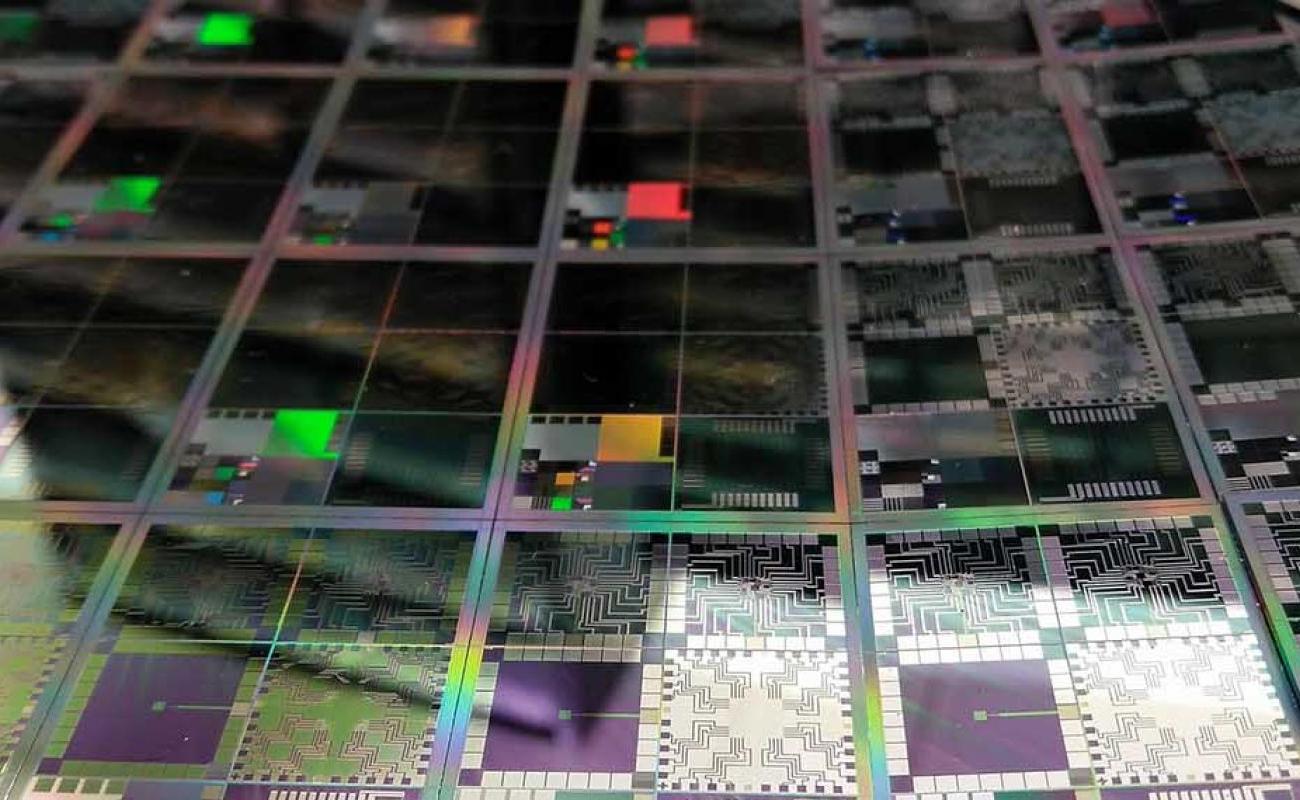

Assessment of global semiconductor supply chains

For decades, governments have developed digital agendas, but semiconductors were hardly a central element in any strategy. However, the COVID-19 pandemic triggered an unprecedented digital transformation across services, sectors and applications, as well as a new rethinking over the disruptions and shocks in semiconductor supply chains that a large number of industries depend on, from the automotive industry to shipping and medical devices.

If the European Union accounted for 25% of chip manufacturing worldwide in 2000, in 2022 it accounted for only 8%[1].The EU has several significant players, such as the Belgian research and development institute IMEC, Dutch ASML that produces extreme ultraviolet lithography machines and equipment, or Infineon and STMicroelectronics that are relevant for specific markets such as power semiconductors. However, the EU’s market footprint is still limited in the global semiconductor value chain.

Other, non-European players have major roles[2]. The United States leads most of the research and development, fabless companies, integrated devices machines (IDMs) and a part of the high-technology equipment manufacturing. Japan leads in the stage of materials (which is at the high-end supply chain). Meanwhile, Taiwan leads in Outsourced Semiconductor Assembly and Test (OSAT) and in foundries. The most important and edge foundries are based in Taiwan and South Korea, while chip testing and packaging services are in Taiwan and Malaysia. While OSAT is at the lower-end in the value chain, it represents a major chokepoint that may produce blockages and disruptions further downstream if OSAT is not duly produced or distributed across all dependent companies.

China’s multifaceted strategy

In this deeply fragmented global value chain of semiconductors, China’s overall market presence is divided in two blocks. On the one hand, China has certain leadership in trailing-edge (20-45nm) and mature nodes (>45nm), or in other words the older generation of semiconductors which is still essential for basic goods such as domestic appliances. On the other hand, its market share and profitability are still low in high-end semiconductors, which have become the core of the current geopolitical competition. While the country hosts most of the critical raw materials that are necessary for chip manufacturing, such as gallium and germanium, no Chinese company has a leading role in any of the sub-stages of the value chain in high technology.

While it remains essential to not overlook the older generation of semiconductors because they feed traditional industries, this paper focuses on cutting-edge, highly advanced semiconductor value chain (<17mn>

China’s main import item are semiconductors ($33 billion per year), which in 2015 for the first time surpassed oil as the country’s largest import. At the same time, China is also the largest global consumer of semiconductors (representing 40% of global semiconductor sales). Although its fabrication capacity grew to 24% in 2021, and it has attained relevant >7nm chip-making capabilities since the injection of national public funds into Chinese companies, the share of fabrication capacity for the most competitive chips is located in other countries. Chips with <3nm>

The country has approached semiconductors through a number of initiatives drawn from the government’s industrial policy. Based on the Made in China 2025 strategy, and the “National Guideline for the Development and Promotion of the Integrated Circuit Industry” by the State Council in 2014, the Chinese government has aimed at reducing import reliance in the Chinese chip industry. Concretely, two integrated circuit funds (Big Funds) have been channelled at the national level, in addition to at least 15 local government funds at the city and provincial levels. Both national big funds and local government funds reportedly accounted for USD 150 billion in a six-year timeframe from 2014 to 2020. Government-supported funding is accompanied by government grants, low-interest loans, and tax incentives (such as tax breaks and below-market rates).