Europe’s new war with Russia: Deep sea sabotage

Before Russia bulldozed its way into Ukraine, Ilja Iljin mainly hunted for people stranded at sea. Now, he also hunts saboteurs.

Iljin, a deputy commander of Finland’s coast guard, is increasingly on the lookout for tankers about to commit sabotage. Behind him is a small army: dozens of radars and cameras, numerous patrol boats, a fleet of planes and helicopters — all deployed to scour a stretch of water as large as Belgium.

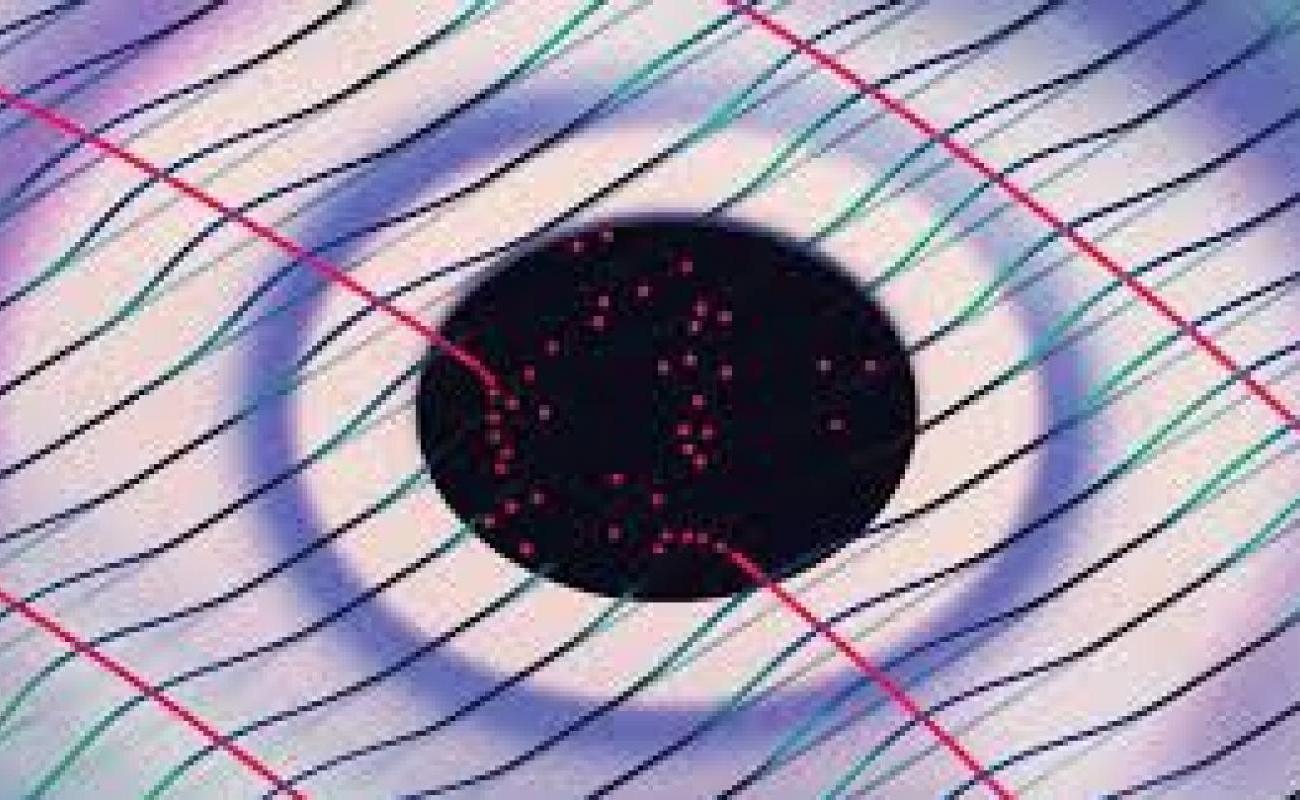

They’re looking for suspicious behavior that could imperil the undersea cables that bring internet and power to Europeans.

And yet, sabotage keeps happening — twice in the Gulf of Finland alone in the last 18 months, according to Iljin. In total, the Baltic Sea has registered at least six suspected sabotage incidents since 2022, with 11 known undersea cables taken out since 2023.

“This is becoming more common,” Iljin said, standing in the cabin of the 23-meter-long patrol vessel, waves chopping against its sides. “We have become more aware of the risk, and we’re currently trying to figure out ways for how to properly respond.”

The damage hasn’t disrupted society. The lights stayed on; the Wi-Fi still worked. But they still sent a chill through Europe: What if the next vigilantes were more coordinated, more severe? What if Russia was launching an assault on Europe? What if it meant war?

A tumultuous scenario is not hard to envision. Ireland could lose a 10th of its electricity via three cable cuts. Norway feeds the European Union a third of the bloc’s gas through underwater pipelines. Going after either target could wreak chaos — energy shortages, runaway prices, forced choices over who loses power.

“We are witnessing … [a] new reality,” said Lithuanian Energy Minister Žygimantas Vaičiūnas. “We have more and more incidents in the Baltic Sea, which could have an impact for markets, for consumers and also for our businesses.”

So far, authorities have failed to conclusively show Moscow was behind any of the incidents. But “such sabotage activities in the current circumstances could be seen as useful for Russia … that’s the only interpretation,” Vaičiūnas told POLITICO.

For Russia, the drumbeat of even minimal damage helps feed Western insecurity — and plant the idea that, true or not, Moscow could upend Europeans’ daily life if it wanted.

Europe’s waters, in other words, have become a new front in the warming Cold War with Russia.

The EU and NATO are racing to tackle the problem, rolling out plans to buy spare cables and drones and beef up military surveillance. But Donald Trump is sparking fears that the situation will only get worse, as the United States’ president trashes America’s core alliances and parrots Russian talking points.

“They’ve been emboldened,” said one EU diplomat, who was granted anonymity to speak freely. “So it just means that we have to get serious.”

Finding cracks

The EU faced its first rude awakening in late 2022.

In September of that year, the Russia-to-Germany Nord Stream pipelines were mysteriously blown up. Reports have since linked the incident to Ukrainian nationals, though the criminal case is ongoing.

Since then, Baltic Sea sabotage has proliferated, hitting telecom, gas and power links connecting Sweden, Finland, Germany, Latvia and Estonia. Just a few weeks ago, a communications cable linking Berlin and Helsinki was again damaged off the Swedish coast.