Chinese Influence in the Western Balkans and Its Impact on the Region’s European Union Integration Process Part III

This regional platform brings together a very diverse group of countries, 11 European Union (EU) countries and 5 non-EU, from the Baltics to the Balkans. Concentrated on trade, investment, and transportation networks, 16+1 supports Beijing’s diversified strategy in Europe by allowing it to focus capital investments for strategic assets and new technologies in the core EU countries, complemented by large infrastructure projects on its periphery.

The geo-strategic position of the Western Balkans is perfect as a bridgehead to EU markets, and a key transit corridor for the Chinese BRI. Chinese interests in the region are strongly related to infrastructure projects and privatization opportunities, where demand for preferential lending is high and acquisition prices are low. Beijing is also searching for new markets to expand its exports and strategic assets in the front yard of the EU, and Chinese companies are securing access to natural resources and focusing on strategic sectors such as energy, mining, and mineral processing. Beijing wants to increase its influence and deepen its economic, cultural and diplomatic presence in a region that is geo-strategically important because of its proximity with the EU, but also as a counterbalance to the region’s transatlantic relationship.[1]

A short historical background

China is not a newcomer in the Western Balkans. While diplomatic, economic and cultural ties with Beijing have existed for decades for Albania and the countries of the former Yugoslavia, activities in recent years have shown that China is laying the groundwork for a long-term, multi-faceted, and ever-deeper presence in the Western Balkans. In its narrative, Beijing aims at highlighting the shared socialist past towards the Western Balkans, using the existence of some degree of post-communist nostalgia in the Balkans, focusing on “traditional friendship” and a “shared past”.

Diplomatic relations between China and Albania officially began in 1949, and grew stronger based on the shared communist ideology. The split of Enver Hoxha’s led communist Albania with the Soviet Union in the early 1960s, opened the way for a stronger and exclusive relationship with Mao Zedong’s China. Those years were characterized by a multi-domain cooperation between the two countries, as Beijing became the key supporter of an isolated Albania, providing large loans for the heavy industry and the military industry, with big arsenals of arms and ammunitions. An important agreement was signed in 1961, where China pledged technical support to Albania for building of industrial plants and factories (chemical, food, clothing, construction materials, and steel mills). Trade volume between the two countries increased as Albania would export raw materials (oil, chrome, and copper) and mainly import industrial products and pharmaceuticals. Strong cultural links were developed during the two decades of intensive friendship, until the relationship fell apart in 1978 due to ideological disputes. Albania isolated itself further from the rest of the world until 1991, and the relationship with China never have reached that past high level.

The Sino-Yugoslav diplomatic relationship, although at good levels during the 1960s and the 1970s, became closer after the breakup between Beijing and Tirana. In 1977, Yugoslavia’s President Josip Broz Tito visited China for the first time, followed by a return visit of Chinese Prime Minister Hua Guofeng to Belgrade in 1978. Ties were strengthened in the mid-1990s, when the isolated former President, Slobodan Milosevic, found an ally in faraway China, and opened the door for the first Chinese migrants in Serbia. The alliance was further forged politically during the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999, when a bomb part destroyed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese citizens inside it. Today, China is considered a strategic partner for Serbia, and the latter has become the biggest beneficiary of Chinese investments in South-Eastern Europe.

Trade between China and the Western Balkans: Higher deficits for the region

China looks at the region primarily as a market for its own exports and as a large window into Western European markets. The Western Balkans market is a small one, where all six countries represent less than 18 million consumers, with a total Gross Domestic Product of $132 billion in 2021, where Serbia makes up almost 50% of the regional market. The entire regional market represents less than 1% of the European market of $17 trillion.[2] In the last 30 years, the economies of the region have experienced high growth rates allowing some sort of convergence with the EU countries, but incomes per capita are very low compared to European standards, with only $7,200 as a regional average, representing less than 15% of the average EU incomes, in current prices (EU GDP per capita $48,750 in 2021).

As countries are falling into the “middle income trap”, the regional convergence with Europe has stalled (regional economic expansion will be 3,7% in 2022-2023), implying that it would take at least 20 years for the Western Balkans on average to double its income, and more than 50 years to catch up with the European average. The dire economic situation is a result of un-friendly business environment characterized by weak institutions and the rule of law, high levels of corruption, and the very limited role of innovation – all factors contributing significantly to the low competitiveness of the region (lowest rankings in institutions and innovation capabilities), shown by the Global Competitiveness Report.[3] Unfortunately, small and fragmented markets, coupled with a harsh business environment, cannot repay costly innovation investments, stymying any significant modernization.[4]

Economic convergence with the West has stalled as a result of non-sustainable economic growth rates, and a triple dip economic recession since the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (Figure 1 and 2). The economies of the Western Balkans were not functioning well before the pandemic. At first sight, most countries have shown moderate growth trends in the past two decades but these are not normal balanced economies. Much of the positivity has been buoyed by a blend of remittances from its expatriate workers, citizens working within well-entrenched informal economies, and more recently, an added dimension of a growing amount of money laundering that is propping up real estate prices and artificially inflating property prices.

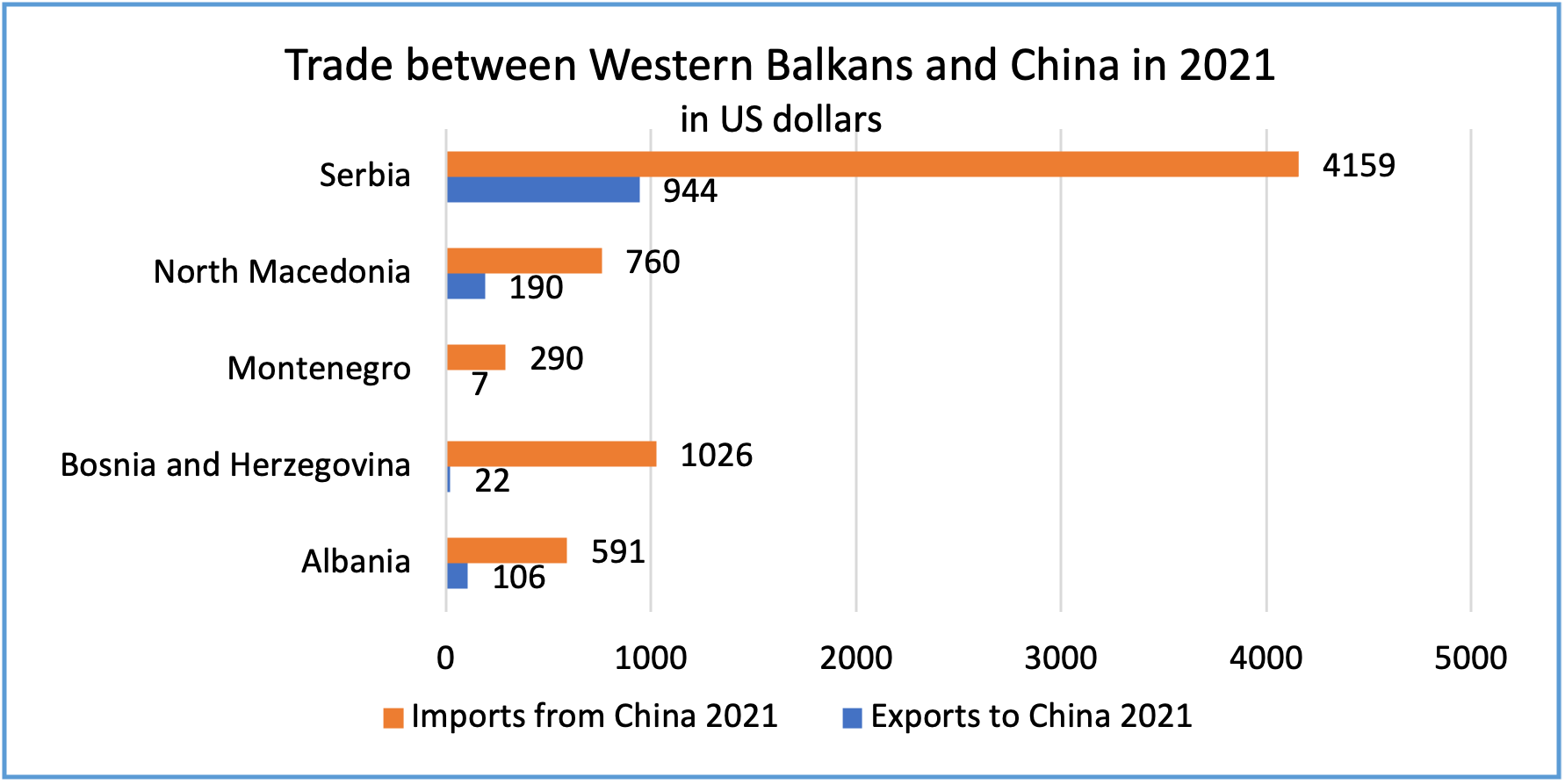

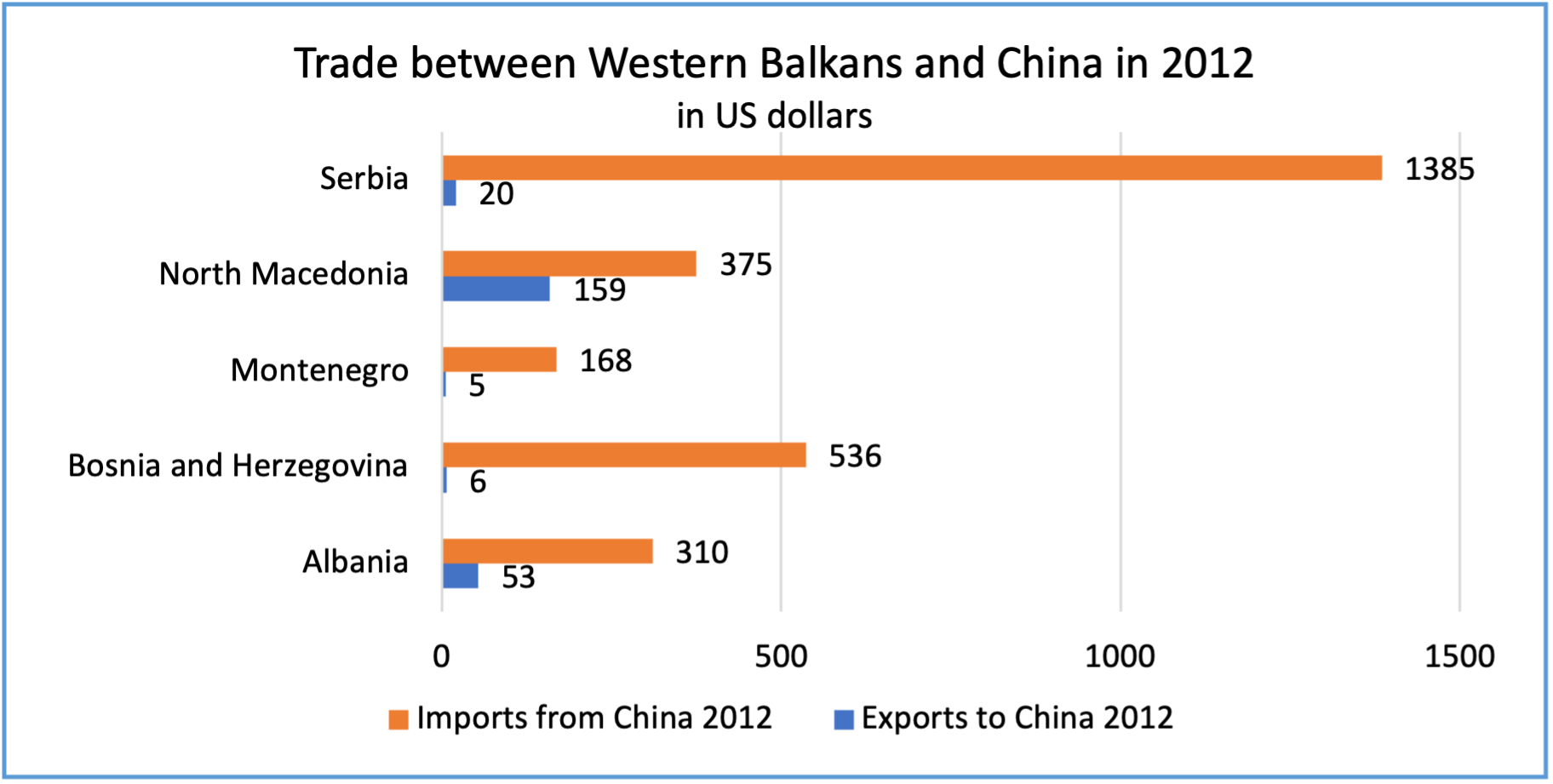

Considering the small regional market, trade exchanges with China have seen a rapid expansion, with an increase of almost three times since 2012, going from $3 billion to $ 8billion in 2021, according to UN Comtrade data (Figure 3 and 4).

Source: UNComtrade database

Source: UNComtrade database

While exports from the Western Balkans towards the Chinese market have increased over the years, the actual trade balance is very heavily tilted in favor of China (for almost 85% of trade).

This means that trade deficits towards China have risen tremendously, as regional exports into the Chinese market amounted to $1.2 billion, while imports of Chinese products in the Western Balkans reached $6.8 billion, in 2021. Nearly 60% of the trade with the Western Balkans is conducted with Serbia ($5.1 billion), China’s main strategic partner in the Balkans.

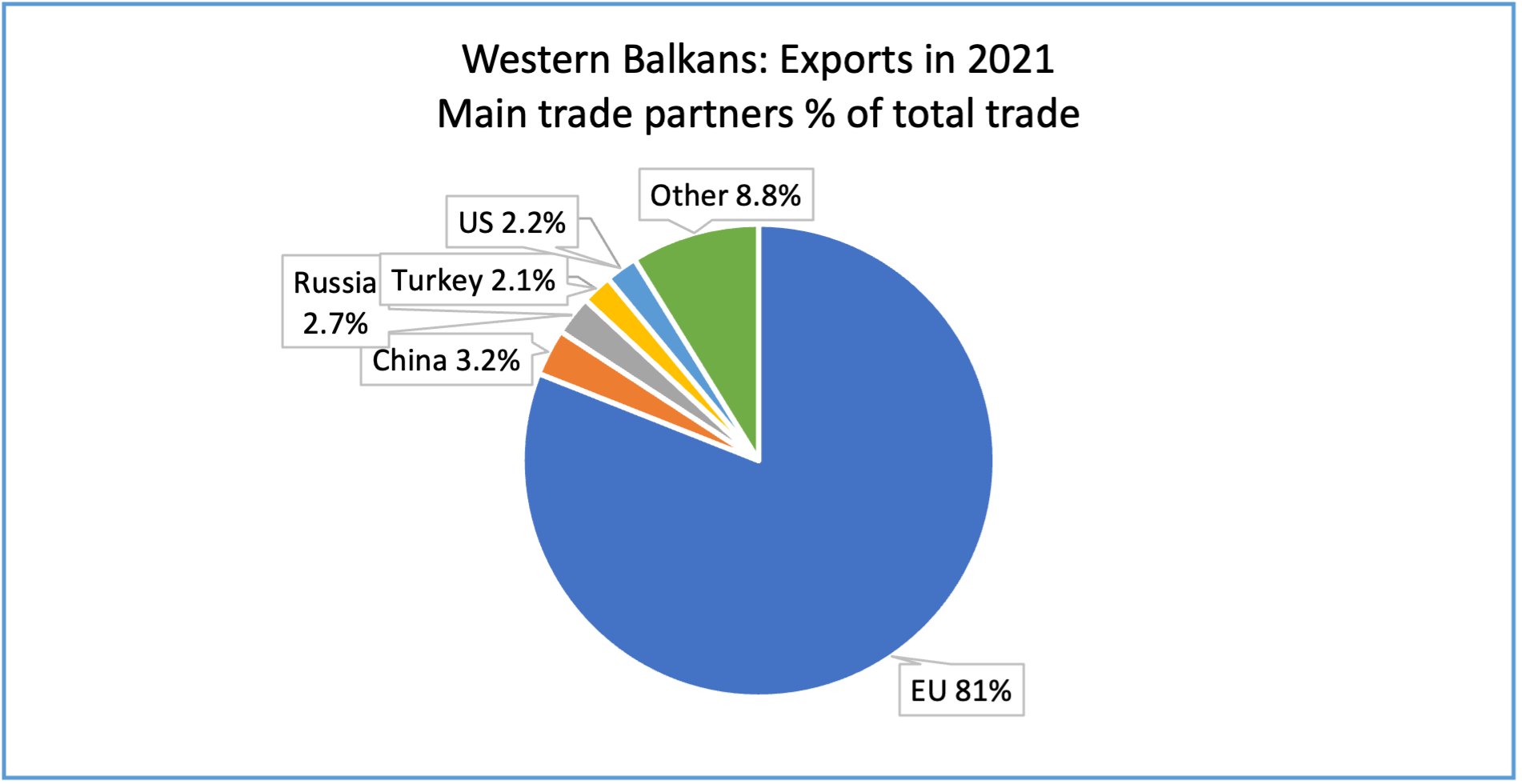

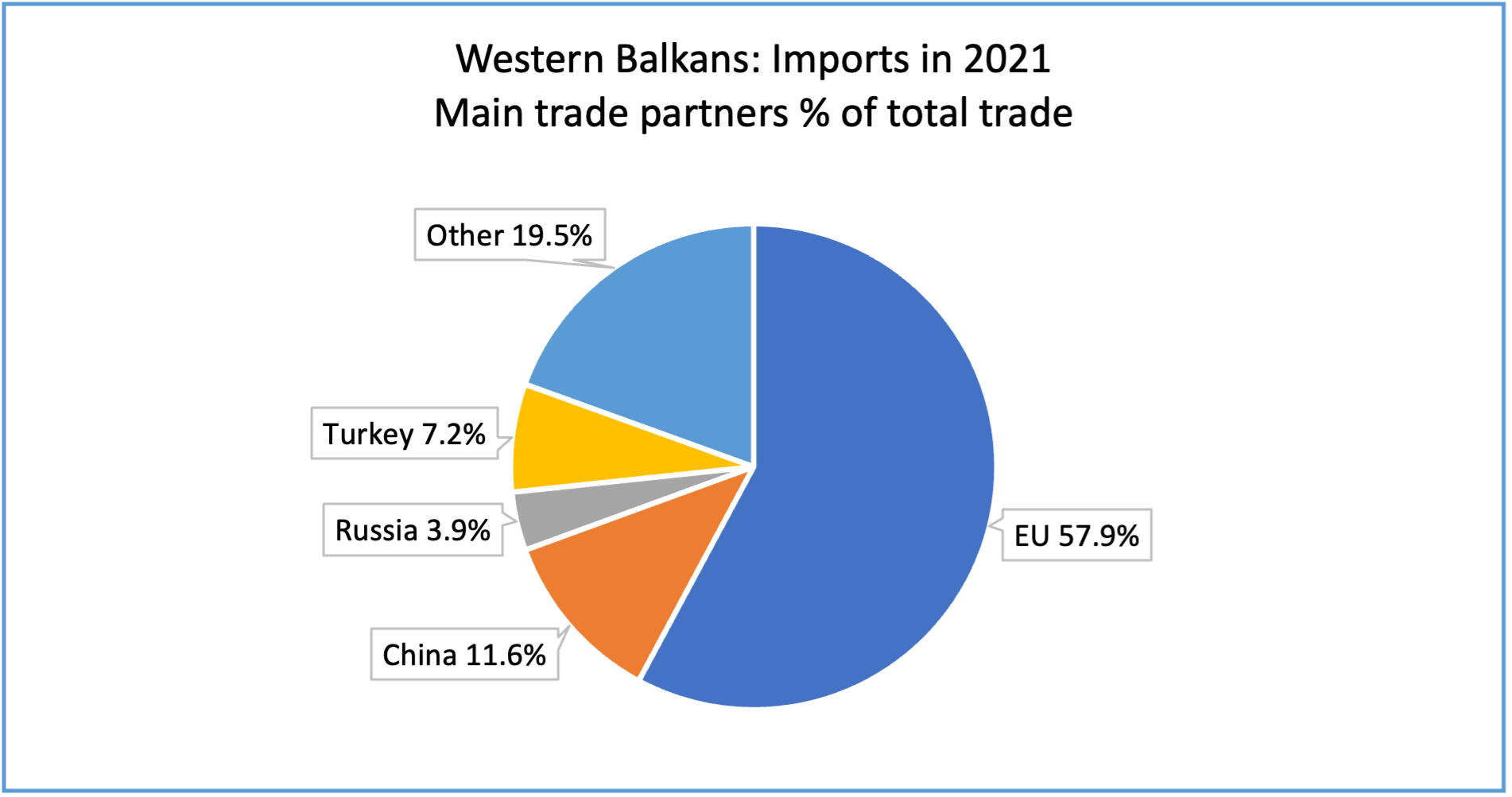

While the EU remains the main trade partner for the region with over 70% of its engagement, both for its exports (81%) and imports (58%)[5], China has quickly become the second or third largest trade partner for the region.[6] In term of European comparisons, trade with the Western Balkans makes up less than 1% of EU-China trade levels ($770 billion in 2021, according to Eurostat data[7]) (Figure 5 and 6).

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/5/5c/Western_Balkan_countries_trade_with_main_partners,_2021.png

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/images/5/5c/Western_Balkan_countries_trade_with_main_partners,_2021.png

Given the need for investment and the low production prices in the region, in the future we might see a trade-substituting investment strategy that could potentially allow Chinese companies to circumvent trade restrictions and export products directly to a market of 800 million people, thanks to the free trade agreements (FTA) that the Western Balkans countries enjoy with the EU.

Chinese Investment in the Western Balkans

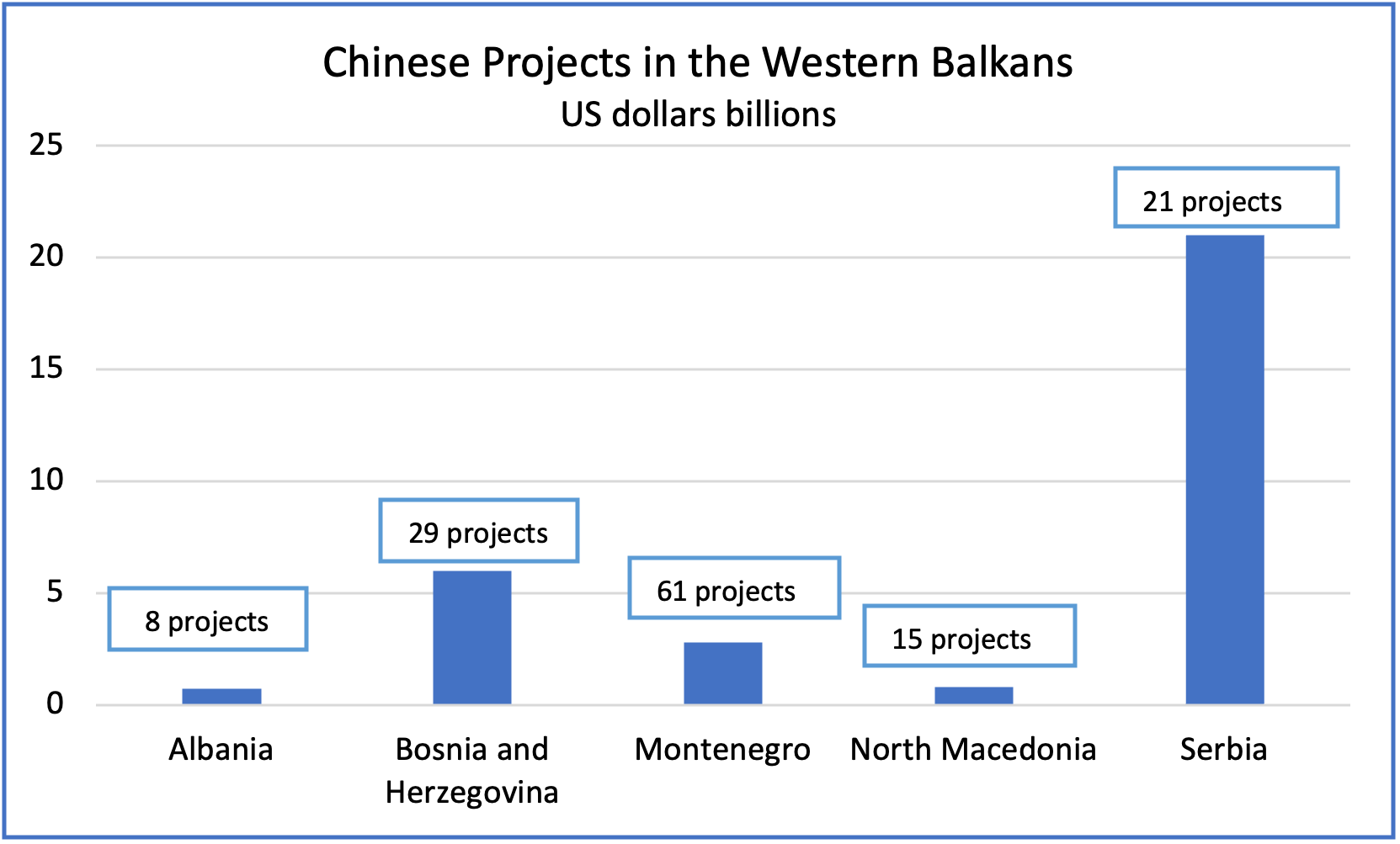

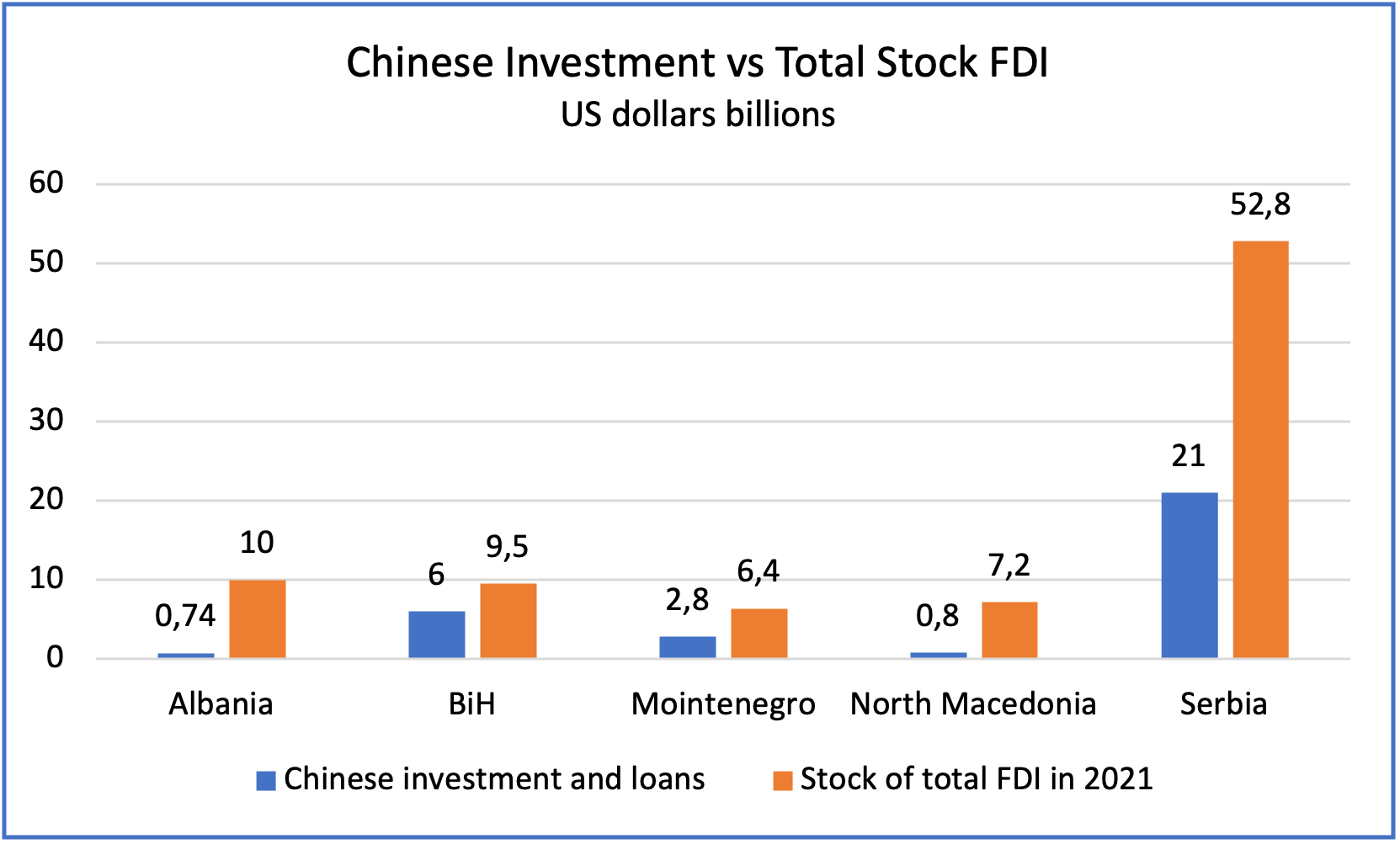

More than trade, there has been a rapid Chinese expansion in investments in the Western Balkans. According to Balkan Investigative Reporting Network data, there are currently about 122 Chinese projects with an estimated value of around $31 billion.[8] This would make up almost 40% of the total stock of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the five Western Balkan countries (excluding Kosovo), which amounted to $86 billion in 2021, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (Figure 7 and 8).

Source: BIRN Data on Chinese investments. Total projects 122 for estimated value of USD 31 billion (27.6 billion Euro)

Source: BIRN Data on Chinese investments. Total projects 122 for estimated value of USD 31 billion (27.6 billion Euro); UNTCTAD data on Foreign Direct Investment.

The entire region has attracted less than 0.2% of the global stock of FDI, despite its geo-strategic position in Europe, where the EU is one of the most important markets for the attraction of FDI with more than 25% of the stock of global FDI in 2021. On the other side, the European countries are among the main investors in the global economy, with almost 32% of the stock of outflow investment in the global economy.

A misleading aspect of the data above on Chinese investment in the Western Balkans is that most of the money is not actual FDI, but loans. In fact, the main form of Chinese economic cooperation in the region is concessional lending for infrastructure, mainly in transportation and energy, through its state-owned banks, and financial vehicles, including the Chinese Development Bank, China’s Exim Bank, the Silk Road Fund, and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

The main sectors for economic cooperation are infrastructure, energy, mining and mineral processioning, and communication technology, while engagement is mainly on a government-to-government basis. Investments in the health sector, educational, and cultural centers are also present. In spite of all the activity, few projects have been concluded, most have been delayed, some have stalled, and for others, given the lack of transparency surrounding these projects, the status is unclear. Allegations of corruption, environmental pollution, and workers exploitation appear to be part of the overall fabric of these investments.

Western Balkans: A perfect testing ground

The Western Balkans has been a perfect testing ground for Chinese investment in infrastructure. China's first big infrastructure investment project in Europe was the Pupin Bridge in Serbia carried out by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), inaugurated in 2014. The first railway project in Europe by a Chinese state-owned Enterprise using funds from the EU was the 10 km segment of Kolasin-Kos railway implemented by China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) in 2017.

The same company, CRBC, wan the bidding contract to build the 2.4 km Pelješac Bridge in Croatia that connects the southern part and Dubrovnik with the mainland, which was inaugurated in July 2022. It was one of the largest EU-funded projects, with $424 million from the Cohesion Policy Funds, as the EU contribution covered 85% of the cost.[9] Called by many “ the Chinese bridge”, only the knowledgeable few knew that this was actually an EU-funded project. The awarding of the contract to a Chinese SOE has led to concerns about Chinese state funding and subsidies, and lack of transparency over the bidding process.

Chinese SOEs are able to take advantage of the lack of transparency and engage in direct contract negotiations throughout the region. Experienced in infrastructure development in other developing countries, Chinese SOEs enjoy economies of scale and can offer cheaper prices subsidized from the Chinese government interested in exporting its excess capacities and construction material they can easily outcompete western companies. The experience in the region has been important for Chinese companies also to familiarize with the EU standards, from public procurement contracts, to labour and environmental standards, and with EU practices and regulations. The difference is that China can still deploy in the Western Balkans its loan-contact model, but in the EU countries public procurements laws prohibit these practices.

As a result, the EU Council and the EU Parliament reached in June 2022 a political agreement to come up with new regulations on foreign subsidies from third countries, “Regulation on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market”, that sought to prevent them from distorting competition for public contracts in the EU.[10]

Western Balkans’s infrastructure: A very important piece of the BRI puzzle

China is attracted to the Western Balkans for its geo-strategic location and the proximity to the EU markets. In line with its BRI objectives, Beijing is heavily investing in large-scale infrastructure projects and taking advantage of the urgent needs for infrastructure in the Western Balkans.

Beijing is developing the 21st Century Silk Maritime Road or the China-Europe Land-Sea Express Route (LSER) as one China-EU trade corridors of the future, an important component of the BRI that links China with Western Europe via the entry port of Piraeus in Greece and the infrastructure networks in the Balkans, through North Macedonia and Serbia into Hungary. The Chinese state-owned China Overseas Shipping Group Cp. (COSCO) has a controlling majority (67%) of the Port of Piraeus[11], and it has become the main entry point for Chinese goods in Europe, shortening normal shipping times by one week. Chinese goods travel by sea into Piraeus, and are transported by train through Serbia and North Macedonia into Hungary and the Czech Republic. In 2019, COSCO also bought a 60% majority stake of the Greek railway company Piraeus Europe - Asia Railway Logistics (PEARL) and a minority stake in the Budapest train terminal in Hungary. Chinese SOEs have also a minority stake in the Port of Thessaloniki in Greece.

China’s long-term strategy in the Balkans views Serbia as a strategic European transportation hub. With 61 projects valued at more than $21 billion, the most significant is the upgrade of the Belgrade-Budapest railway. In the Western Balkans, one of the biggest projects is the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway, agreed in the “16+1” Summit in Riga in 2016, to be financed 85% by China Exim Bank (USD 2.5 billion) and implemented by China Railway and Construction Corporation. For two sections of the Belgrade-Budapest highway, Serbia has already borrowed $1.5 billion. Another important Chinese transportation project in Serbia includes the modernization of the 204 km railway line between Belgrade and Nis, as part of the European Corridor X that connects Salzburg in Austria with the port of Thessaloniki in Greece. The project is estimated to cost more than 2 billion euros, and is discussed to be implemented by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC). The only completed infrastructure project in Serbia is the Pupin Bridge, China's first big infrastructure investment in Europe as opened by PRC Premier, Li Keqiang, and Serbian President, Aleksandar Vucic, in December 2014, implemented by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC).

North Macedonia is also an important country in the BRI framework. In 2013, the Government of North Macedonia borrowed more than $800 million from China’s Exim Bank for the construction of two highways. The Miladinovci- Shtip was completed in August 2020, and the Kichevo- Ohrid highway (an integral part of European Corridor VIII) is yet to be completed, while construction costs have increased and could rise to $1.2 billion (if interest payments are included), implemented Sinohydro Corporation. Both projects have been overshadowed with corruption allegations.

In Montenegro, the Bar-Boljare highway is the biggest Chinese project linking the port of Bar in the Adriatic Sea with Serbia, financed by China’s Exim Bank for almost $1 billion (only for the first section of the highway, making it one of the most expensive highways per km in the world with $20 million per km), and being built by the China Road and Bridge Corporation (RBC). This financially unsustainable project signals the Chinese interest in the port of Bar. With only 41 out of 165 km completed, “the road to nowhere” had raised questions about the financial feasibility of the project and the unsustainable debt associated with it, sending Montenegro’s sovereign debt rocketing to 103% of economic output. According to estimates of the Montenegrin government, the remainder of the highway will cost an additional USD 2 billion.

Chinese companies have also been involved in upgrading the railway network in Montenegro. China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) completed in 2017 the reconstruction of a 10-km segment of the Kolasin-Kos railway for $8 million. For Beijing, it was a very important project as it represented the first railway project in Europe by a Chinese company with funds from the EU.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chinese construction companies are involved in the construction of the 12-kilometre-long Počitelj–Zvirovići section of a highway at a cost of $75 million (EUR 66 million), financed by the European Investment Bank.

In Albania, China Everbright, a Chinese state-backed company bought all the shares to run Tirana International Airport from AviAlliance GmbH (A German-American investment) for $90 million, the then sole airport in the country[12]. This was China’s major investment in airport infrastructure in a NATO country. Only four years after under unclear circumstances, the Chinese company sold the concession fully to a local one for a transaction that was valued about $80 million (EUR 71 million).[13]

Investment in infrastructure is a public good that could foster sustainable economic development, but the positive developmental spillovers depend on the practical details of implementing these projects, and the institutional absorptive capacities of the host countries. Considering the huge infrastructure deficits in the Western Balkans, Chinese state backed enterprises can easily outcompete western companies with their opaque way of doing business with established political elites, enabled by high levels of corruption in the Western Balkans, taking advantage of existing problems of a lack of transparency in the region. Chinese SOEs engaging in infrastructure have acquired experience in other developing countries and have advantages of scale offering cheaper prices as a direct result of state support interested in exporting its excess industrial capacities construction, steel, and cement.

Chinese interests in Energy and Mining

Another important pillar of China’s expansion policy concerns securing its present and future demands for commodities, mainly by investing in countries rich in natural resources such as steel, cooper, and oil. The Balkan energy sector is also very attractive for Chinese SOEs, as major western utility companies are unwilling to make risky investments. Albania, Montenegro and Bosnia-Herzegovina are attractive for their hydropower capacities while North Macedonia and Serbia and Croatia for their wind energy potentials. Chinese investments in these areas are mainly focused on acquisitions and privatization.

In 2016, China’ state owned Hesteel Group took over Smederevo’s steel mill for $55 million, a former US investment that was sold back to the Serbian government in 2012 for a symbolic value of 1 dollar. The company pledged to keep on the 5000 workers, and President Xi Jinping. HBIS Group Serbia has become Serbia’s biggest exporter company. Another important investment in Serbia’s mining industry is Zijn Mining Group that holds the controlling majority in RTB Bor copper factory, for an estimated investment of more than USD 1 billion, including plans of expansion. Shandong Linglong is the main company involved in major green field FDI in the region, with a tire factory in Zrenjanin, an investment of around $900 million.

China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) is building a third, 350 MW unit at thermal coal power plant of Kostolac (east of Belgrade) with a $600 million Exim Bank loan, as well as the expansion Drmno open cast lignite mine in the Kostolac basin. As Serbia meets 70% of its electricity with lignite, concerns have been raised that Chinese investment in coal plants and mines are delaying the coal-out phase and hindering Serbia’s progress away from fossil fuels, while undermining its pledge to combat climate change as these investments are breaching the EU environmental laws in the region. Concerns related to environmental pollution have sparked protests, despite the fact that these are significant investments for the Serbian economy and have contributed to the rise of local employment.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, Chinese interests have focused on two big energy projects, the Stanari coal power plant (in 2013 for $400 million financed by China Development Bank) and the Tuzla lignite power plant (in 2017 with a first loan of $800 million from Exim Bank and implemented by China Gezhouba Group, part of China Energy Engineering Corporation), accumulating for the small country a debt of more than $1.2 billion (13% of BIH’s external debt) and becoming an iconic example of the clash between Chinese investments and EU environmental standards [14]In fact, four years after the approval of a public guarantee for the Tuzla 7 lignite plan, the State Aid Council of Bosnia and Hercegovina revoked the approval of the loan, a decision that settles an infringement procedure launched by the Energy Community Secretariat in 2019, considering the “negative impact on the interest of all citizens in Bosnia and Herzegovina as air pollution is responsible for severe health and environmental damages”[15] Preliminary contracts have been signed on other multiple thermal plants, but few have been implemented, such Ugljevik III was reportedly financed with a $782 million loan from China Development Bank (CDB), but it has not been executed.

In 2020, the government of the Republika Srpska (one of the two political entities that make up BiH) signed an agreement with China Gezhouba Group for a USD 216 million investment to [C1] to build the Dabar hydropower plant in the country’s south. Another investment from China Electric and Polish-Chinese firm Sunningwell International has been announced for the construction of the Ugljevik 3 thermal power plant[16].

In Albania, the Chinese Geo-Jade Petroleum, a Chinese private enterprise that entered in the oil business in 2013, owns the concession to extract oil in Patos-Marinza oil field (since 2016), the biggest field in the country producing 95% of Albania’s crude oil and accounting for 11% of its exports.[17] This is also one of the largest onshore oil fields in continental Europe. The company also owns Kucova and Block F fields. The concession price was around $442 million but it was bought from Bankers Petroleum, a Canadian company. As a result, this does not appear in data as a Chinese FDI in Albania, and the name of the company was not changed by the Chinese owners, going under the radar. According to Bankers Petroleum, this is the largest foreign investor, largest taxpayer and one of the largest employers in Albania, but recently the company has run into environmental problems and was fined from Albanian state authorities.[18]

Another Chinese investment in the Albanian mining sector relates to copper, as in 2014 Jiangxi Copper Corporation, the largest copper producer, manufacturing and distributing copper products in China) bought 50% of the stakes (for a price of $65 million) of a Turkish mining company operating in Albania, owned by Turkish “Ekin Maden”, operating in Albania in Albania in a partnership with Beralb Sh.A.S[C2] ”[19]. The Turkish-Chinese joint venture is the leading company for the exploration and processing of copper and has a concession until 2043 for several copper mines and plants in Albania.