China’s Wagner? Beijing Establishes Private Security Company in Myanmar

China is collaborating with the Myanmar military junta to establish a joint security company to protect Chinese investments and personnel in Myanmar. On October 22, 2024, the junta formed a working committee to draft a memorandum of understanding (MoU) for the initiative, reflecting China’s growing concerns over the security of its projects, particularly those under the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor.

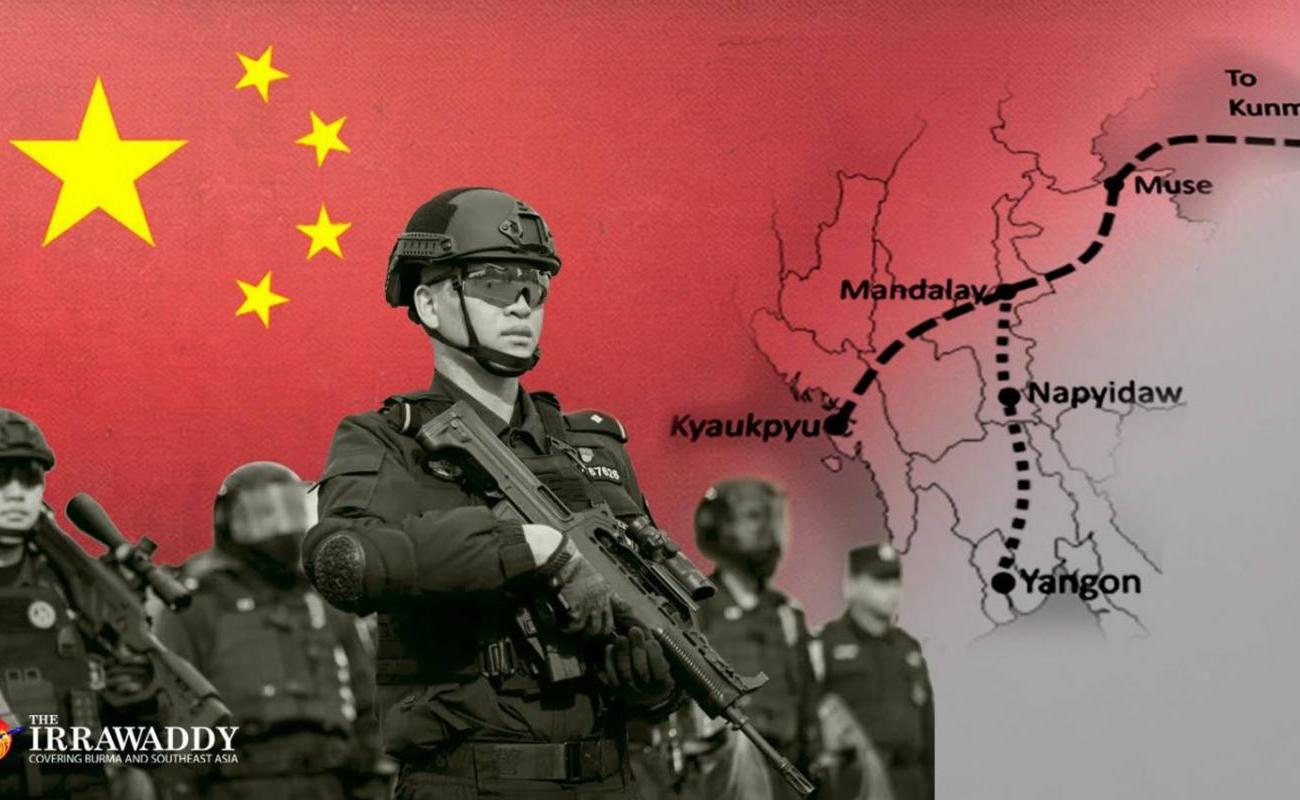

As a key part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), CMEC comprises highways, railways, pipelines, and economic zones connecting China’s Kunming province to the deep-sea Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar’s Rakhine State. The economic corridor is vital to Beijing, providing direct access to the Indian Ocean and bypassing the strategically vulnerable Malacca Strait, a chokepoint critical to China’s energy and trade supply lines, particularly in the event of a conflict with the United States. Yet unfortunately for Beijing, many CMEC projects pass through some of Myanmar’s most volatile conflict zones.

Since pro-democracy opposition armies declared a “people’s defensive war” in 2021, Chinese projects, including oil and gas pipelines, have come under increasing threat. Notably, in January 2022, a local People’s Defense Force attacked the $800 million Tagaung Taung nickel processing plant. More recently, the Chinese consulate in Mandalay was damaged in a bombing attack last month. While no group has claimed responsibility, both the People’s Defense Forces and the National Unity Government (NUG) have condemned the incident.

The announcement of a joint security company has sparked controversy in Myanmar, with many arguing that it could be perceived as a breach of the country’s sovereignty. Myanmar’s 2008 constitution prohibits the deployment of foreign troops on its soil, and the framing of this initiative as a Chinese “company” in a joint venture appears to be a strategic move to deflect accusations of a foreign military intervention. By structuring the company as private and partially Burmese, Beijing can claim arm’s-length deniability, distancing itself from direct involvement while potentially directing the security force to carry out state-derived foreign policy objectives.

The deployment of a Chinese private security company (PSC) comes at a critical moment in the Myanmar civil war, and amid sustained financial and military support for the junta, including shipments of weapons and aircrafts. But above all Beijing’s motivation for establishing the joint venture signals waning confidence in the junta’s ability to protect Chinese investments and personnel. Such concerns are underscored by the junta’s overstretched military forces, which have lost significant ground and numerous bases and outposts to pro-democracy rebels, further eroding the junta’s presence across Myanmar.

In late October 2024, Chinese authorities reportedly placed Peng Daxun, commander of the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), under house arrest in Kunming, Yunnan Province, to pressure the group to withdraw from Lashio. The MNDAA’s capture of Lashio in August 2024 dealt a major blow to Myanmar’s junta.

Lashio, a strategic hub in northern Shan State, serves as a gateway to China’s Yunnan Province and central Myanmar along the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). Its control is vital for ensuring the flow of Chinese investments and trade. China frequently claims to adhere to its official stance of non-intervention in the sovereign affairs of other nations, yet developments in the Myanmar civil war suggest an active involvement. By detaining Peng Daxun, Beijing seems to be stepping in where it perceives the junta has failed, underscoring its wider rationale for establishing a private security company in Myanmar.

Beijing already has numerous private security companies operating globally, including four in Myanmar, in areas where China has significant strategic and economic interests. The largest Chinese security companies include De Wei Security Group Ltd, Hua Xin China Security, Guan An Security Technology, China Overseas Security Group, and Frontier Services Group.

The idea of a Chinese security company is reminiscent of Russia’s Wagner Group, a private military company (PMC) that has been heavily involved in conflicts across Africa, the Middle East, and Ukraine. Wagner functions as an unofficial extension of Russian state power, providing military training, combat support, and securing strategic assets, often under the guise of protecting Russian interests abroad. Its operations frequently involve direct combat roles, covert military activities, and securing resource-rich areas, making it an instrument of geopolitical influence for Moscow.

In contrast, Chinese private security companies primarily focus on safeguarding infrastructure projects, personnel, and investments linked to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Unlike Wagner, these companies avoid direct combat roles, instead specializing in site security, risk management, and logistical support.

However, the proposed firm in Myanmar will be a joint venture with the junta, introducing a new dynamic. It is already known that this company will facilitate arms shipments and deliveries to the junta. As a junta-aligned company, it may operate with fewer restrictions and potentially involve heavily armed personnel, diverging from the usual limitations imposed on Chinese PSCs. The joint arrangement could also mean the company is not bound to adhere strictly to Chinese regulations, raising concerns that it might take on a more militarized role than typical Chinese security firms. In an extreme case, there is speculation that Chinese security firms could take an active role in the junta’s fight against pro-democracy forces, similar to the role that Russia’s Wagner Group has played in its engagements in Africa and the Middle East.

Incidentally, the joint private security company approach is also being attempted in Pakistan, where a string of recent attacks against Chinese citizens and economic interests have shaken faith in Islamabad’s ability to protect the CPEC corridor.

In response to the announcement, Myanmar’s civilian National Unity Government (NUG) asserted that collaborating with the NUG and revolutionary forces is the only viable way to effectively protect Chinese investments and operations in Myanmar. The NUG further emphasized its commitment to safeguarding lawful investments and fostering friendly relations with neighboring countries. The messaging serves to reassure Beijing that, even if Myanmar transitions to democracy, it will continue to maintain trade relations with China.

Yet it seems for now that Beijing is not ready to abandon the junta, and amid a fraught outlook on the battlefield, the deployment of a Chinese private security company is the only way to ensure the junta’s survival. For its part, the NUG remains isolated, lacking in both recognition from Western powers and a direct line of communication with Beijing.

CONCLUSION

The text about the establishment of a Chinese security company in Myanmar, based on an agreement reached with the ruling junta in this Asian country, and under the guise of protecting Chinese investments in this country, actually points to the conclusion that China (in)directly supports the ruling junta. Generally, Chinese investments are most present in countries that cannot boast a high level of democracy, as well as in countries where a high level of corruption and non-transparent business is recorded.

This is also the case in most Western Balkan countries, where the basic characteristics of Chinese companies' business operations are precisely suspicion of corrupt practices and non-transparency. Governments in Western Balkan countries should pay more attention to investments by Chinese companies in their territory, because there is a likelihood that if they conclude that domestic authorities cannot provide them with adequate (according to the opinion of Chinese investors) protection, they will resort to engaging private mercenary companies, which, as in the case of Myanmar, may mean a direct violation of the constitution and sovereignty of the Western Balkan countries.