“You will be taught – and you will become Russians”: how Ukrainian teenagers resist Russian re-education

Mykhailo Lebedev was just 16 years old when Russians captured his city, having subjected it to a relentless campaign of bombardment lasting three months, razing residential areas, hospitals, schools and universities alongside killing tens of thousands of residents. An orphan, Mykhailo was forbidden from leaving his private guardian, because he was a minor. “Mariupol, it was like another world,” Mykhailo recalls. “You saw people walking with satisfied faces, and you were happy to walk along the street. And now there are almost no people in the city, and you see everything is destroyed.”

He attended eighth grade at Mariupol School No. 38. During the Russian occupation he was briefly forced to study at another school as his was one of some 52 that were damaged or destroyed in the city. His school was later restored, and the children returned. However, the circumstances were very different.

The teenager said that at School No. 38, the Ukrainian language stopped being taught and Russian propaganda was widespread. Textbooks were replaced, and teachers were forced to talk about how the Russian Federation came to “liberate” Ukrainians. “Ukraine is bad, Russia came to “liberate” you, that now everything will be good, everything will be good, everything will be wonderful,” he said. Meanwhile, Russians were establishing artillery positions on the school grounds to shoot at Ukrainian soldiers (and which no doubt created another level of psychological distress to both teachers and students). “The Russian army drove onto the school grounds. We had a huge field there – they brought in tanks and armoured personnel carriers and started shelling Azovstal,” he said.

Mykhailo’s sister, Anastasia Lebedeva, asked Anton Bilay, the director of a college in Mariupol, to help her brother leave. He contacted the Ukrainian Children’s Rights Network, a non-governmental organization, and the Ukrainian Ministry for the Reintegration of Occupied Territories, and together they helped the boy leave the occupied territory. He arrived in Khmelnytskyi on Christmas Eve 2023.

Mykhailo is just one of many Ukrainian teenagers who resisted Russia’s system of indoctrination and intimidation in the occupied territories, and despite significant threats, were able to return to free Ukraine. Three of these escapees shared their testimonies with “The Reckoning Project”. They provided further information about the nature of Russian indoctrination in schools, in both the temporarily occupied territories, and Russia itself.

The occupation system

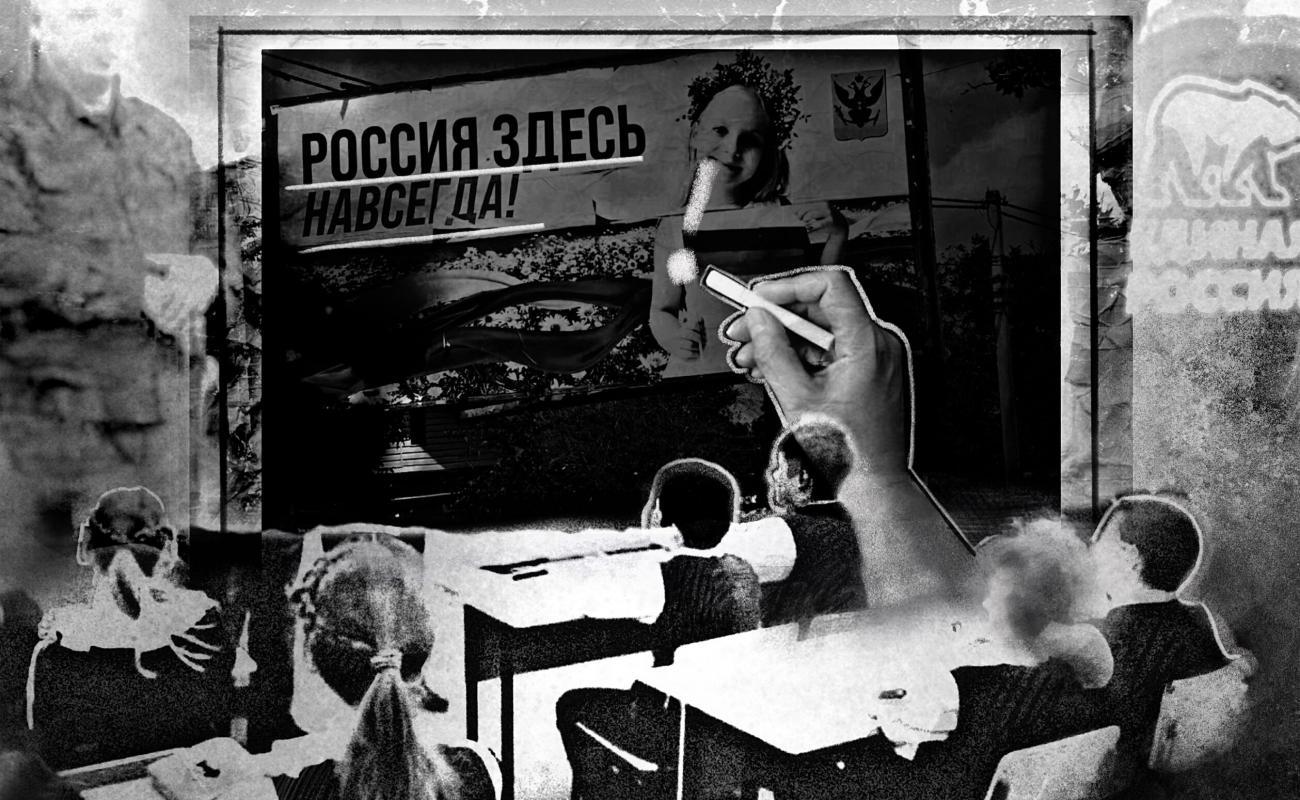

Russia has systematically and intentionally been attempting to erase the very idea of Ukrainian national identity and culture. This has been true in the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas since 2014, and across a wider area following the full-scale invasion of 2022. The occupation authorities have clearly been committing acts in areas under their control which are prohibited in international law – including in the genocide convention – such as forcible transfer. Children are subjected to these Russian methods seemingly aimed at destroying their national group, and nowhere is this more evident than in Russia’s re-education campaigns.

In Ukraine’s temporarily occupied territories, Russia has been purposefully erasing Ukrainian language, culture and identity while promoting a cult of war, glorifying the former USSR (at School No. 65, which Russians destroyed, and then rebuilt, occupiers erected a large Lenin monument), and installing teachers who often bully Ukrainian students (Russian propaganda has been calling Ukrainians “Nazis” since 2014). School administrations quickly try to eradicate all traces of Ukrainian identity, while imposing Russian as the language of instruction. Teacher accounts provided to The Reckoning Project indicate that educators in the temporarily occupied territories have been subjected to extreme forms of intimidation to force them to comply with the occupation authorities’ educational demands. Meanwhile, Russian state propaganda has continually dehumanized Ukrainians by denying that their national identity is even separate from that of Russia’s – all while attempting to erase the very aspects that make it different. A key prong of Russia’s coercive tactics is violence: the threat of violence and willingness to use violence. Russia’s torture chambers in Kherson, southern Ukraine, in 2022 were part of a “calculated plan to terrorise, subjugate and eliminate Ukrainian resistance and destroy Ukrainian identity,” according to an international consortium.

Russia’s mass kidnapping of Ukrainian children is widely known, with both the Russian leader Vladimir Putin and Russia’s commissioner for children’s rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, both wanted by the ICC for the unlawful deportation and transfer of tens of thousands of Ukrainian children to Russia. In August, it emerged that Russia had created a catalogue of stolen Ukrainian kids for Russian families to adopt (and “Russify”), many of whom were orphaned when Russia killed their parents. Sadly, some malleable youngsters who grow up in the temporarily occupied territories and who were re-educated by Russia, have been coerced and manipulated into fighting for those who destroyed their lives, with widespread reports of abducted children being prepared for combat roles. One Reckoning Project interviewee, born in the city of Khartsyzk, Donetsk region, graduated from school in 2020 when the area was already under Russian occupation. They had to study the Russian language and a subject titled “History of the Fatherland”, with the Ukrainian language removed from the curriculum after the sixth or seventh grade. He was deployed to the front lines in early 2024, despite assurances that he would not be sent on combat missions.

These are just recent examples of Russia’s attempt to squeeze any sense of Ukrainianness out of the country’s youth to further its long-term imperial ambitions. Russia did not fully develop its methods of oppression from the murder, imprisonment, deportation and starvation campaigns of the USSR. After all, Moscow’s attempts to eradicate and subjugate nations on its periphery has been ongoing for centuries: tsarist Russia banned any Lithuanian-language publications in the Latin alphabet back in the 1800s as part of its campaign of eradicating national identity and Russification policies to ensure cultural assimilation. In the 1920s and 1930s, the forced starvation of Ukrainians resulted in the deaths of millions, contributing to Raphael Lemkin coining the concept of genocide.

A Russian strategy document signed by Putin, and published on November 25, explicitly laid out the country’s intentions to force those located in the temporarily occupied territories to become Russian, by adopting “additional measures to strengthen overall Russian civic identity” there. The aim is to ensure “no less than 95 percent” of the country’s population identify as Russian by 2036 (Russia claims that the eastern Ukrainian lands it invaded are its “historical territories”).

“I want a Ukrainian passport”

While facing these pressures at school, Mykhailo was also being worn down by his fraught home life, harassed by his pro-Russia guardian. “When the Russian authorities came, she started telling me that the Russian Federation is very good, that Ukraine and America will soon be gone,” Mykhailo said. He found it hard to believe. When the Russians destroyed Mariupol, he also lost his only remaining family nearby: his two older sisters managed to flee to western Ukraine. Then, in 2023 his school started demanding he change his Ukrainian documents for Russian papers, once again bringing him into conflict with his pro-Russian guardian.

“She wanted to change the documents to Russian ones, but she couldn’t do it without me,” he said. “But she knew that I had sisters who had left for Ukraine, and she knew my position. When she started talking about changing passports, I told her categorically: “No, I won’t change it. I want to have a Ukrainian passport.” The guardian threatened him with the police, and his school administration threatened to withhold his ninth grade certificate. He also experienced a top-down effort to encourage peer pressure among students through involving young men and women in youth movements such as Yunarmiya, Movement of the Firsts, and others. Mykhailo recalled that fellow classmates were pressuring other schoolchildren to join the “Young Guard” of Russia’s ruling “United Russia” party, as well as the aforementioned “Movement of the Firsts”.

Subjected to psychological abuse at home, bullying from teachers at school, lessons polluted with Russian propaganda, and peer pressure, Mykhailo naturally had a very, very difficult time, and started skipping classes. His psychological health deteriorated and he recalls becoming very “tired”. “I didn’t want to stay in this house,” he said. Despairing, he entered a local vocational college, where he could live in dormitories.

Children like Mykhailo are not so easily broken, with their age, patriotic upbringing, experiences and memories from before the occupation, and internet access all working in their advantage (though media from outside is increasingly difficult to access as Ukrainian internet providers have been replaced by Russian equivalents). Sometimes the Russian indoctrination systems encourage that which they try to prevent, strengthening teenagers’ patriotism and love for their native language.

Article 50 of the Fourth Geneva Convention (1949), to which the USSR was a signatory, stipulates that occupying powers should ensure that children who are orphaned or separated from their parents, be educated “if possible, by persons of their own nationality, language and religion”. Russia, considered a successor state to the USSR, is still bound by the obligations set out in this treaty – obligations which it is clearly failing to meet. Russia is also a party to the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Articles 28 and 29 state that state parties must recognize the right of a child to education, “and ensure that education fosters respect for the cultural identity, language, and values of the child’s country of origin”. Russia is not honouring this either.

“I am not obliged to stand under this flag”

Valeriia Halych and her mother Nataliia were separated for a year and a half, initially as the result of Russia’s occupation of villages in eastern Ukraine, and then when her pro-Russian father forced the girl and her older brother to leave for Belgorod, southern Russia, where they entered local colleges. Two days prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion, Nataliia took her children to her mother-in-law’s home in the village of Yamy, Luhansk region, believing they would be safer there than in their home city of Severodonetsk, to which she returned. Yamy was swiftly occupied, and Nataliia had to climb high-rise buildings while under fire in the city to communicate with her children. She suffered two contusions and one wound in her attempts to reach them, and ultimately they lost contact.

The children attended a local school for two weeks, where Valeriia said Ukrainian textbooks were replaced by Russian ones, and they were forced to learn the anthem of the Russia-established “Luhansk People’s Republic” (LPR), while Russian history and the Russian language were added as mandatory subjects. Ukrainian history was removed from the school curriculum, and the Ukrainian language limited to grades ten and 11. The school displayed the flags of the so-called LPR, the Russian Federation, and the Red Army victory banner. Later, the children were transferred to online distance learning.

In August 2023, the children’s father, Oleksiy Halych, arrived from Poland, got Russian passports for his son and daughter and took them to Belgorod, Russia. Nataliia Halych said that her ex-husband had previously fought for the LPR, which is viewed as a terrorist organization by Ukraine. Valeriia did not want to go. She cried and begged to be sent to territories controlled by Ukraine. However, her father was inexorable. He took the children to Belgorod, Russia and forced them to enter colleges. Valeriia studied at Belgorod Mechanical and Technological College as a fashion designer, and stayed there from September to October 2023. According to Valeriia’s mother, Ukrainian children were constantly bullied and humiliated in Russian educational institutions, and the degree of propaganda intensified. “You will be taught, raised – and you will become Russians. This is your motherland now. Ukraine is not a state, subhuman, and Ukrainians are pigs,” teachers told Valeriia.

Every Monday, college students were forced to sing the Russian anthem, and raise the Russian flag. They were also forced to undertake weekly lessons called “conversations about the important”, during which Russian culture was imposed on students. “Russian teachers called the war a special military operation, they said that Ukrainian textbooks were written untruthfully. They said that Ukraine started the war, and Russia was not conducting any military operations on the territory of Ukraine. They told us that Russia only “rescues” (this is their favourite idea), it simply protects its territories, they do not touch civilians, they only attack military facilities,” Valeriia stated.

The girl did not like the educational institution. In college, all the textbooks were in Russian, and while she was studying fashion, lessons on the Russian language, Russian literature, Russian history, OBZH (life safety protection), and the “Great Patriotic War” (Russia’s name for the Second World War) were all mandatory. During OBZH classes, she was taught to disassemble and assemble an automatic machine gun. Valeriia Halych had problems in college because of her pro-Ukrainian beliefs. She openly told them, “I do not need this anthem, I will not sing it and I am not obliged to stand under this flag.”

Valeria said that students were sent to “intern” in factories, sewing clothes for the Russian military, and making camouflage nets. They received school awards for what was essentially free labour for the Russian military. Ukraine is also party to the Fourth Geneva Convention, which means its civilians, who “at a given moment and in any manner whatsoever, find themselves, in case of a conflict or occupation, in the hands of a party to the conflict or Occupying Power of which they are not nationals”, count as protected persons. Article 51 stipulates that protected persons may not be compelled to serve in “armed or auxiliary forces” while “no pressure or propaganda which aims at securing voluntary enlistment is permitted”. Protected persons may also not be compelled to work unless they are over the age of 18 – which Valeriia was not.

When Nataliia discovered that her children were in Russia, she naturally tried to get them back, which proved difficult under the draconian nature of their dormitories, where they were forbidden to communicate in Ukrainian. On her first attempt, Nataliia found someone to take her daughter to the border, but she was not allowed through unaccompanied by an adult. She was 17 at the time. After a further failed attempt to get her back via Belarus, which caused Nataliia to almost break down completely, she finally made it to Warsaw, and returned to Kyiv on October 16th 2023.

While she finally finished her 11th grade education remotely from Kyiv, she opted not to enter higher education and take a break after her prolonged period of stress. Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion she had planned to study abroad, but her experiences helped her realize how important it was to her to study in Ukraine. “I also decided to speak Ukrainian. At first, it was very difficult to switch, because I had communicated in Russian all my life. But now I think that language is very important, both our genetic code and our nationality,” Valeriia said.

“I don’t want to be Russian”

One youngster, Kyrylo Kuzmenko (his last name and first name have been changed for security reasons), similarly endured his family being torn apart by Russia and attempts to indoctrinate him while erasing his national heritage. Twelve years old at the beginning of the invasion, Kyrylo lived with his grandparents in a village in Luhansk region as his mother Larysa (also a pseudonym) was serving with the military in a nearby city, though she often visited. Just like Nataliia and Valeriia, mother and son were separated after the full-scale invasion, and Larysa could not enter the occupied territories.

“You know, it was tears and despair,” she said. “Everyone there knew that I was a military woman. And when the territories were occupied, it was clear that anything could happen to the child. And there was no way to pick him up, because the road was closed, because the whole family are military service people.” In September 2022, Kyrylo was allowed to attend a lyceum in the occupied territory with Ukrainian documents. However, the following year the school administration began to demand an LPR-issued birth certificate, threatening him with an orphanage because he did not live with official guardians. The headteacher told him, “if you misbehave in class, you will go to an orphanage,” Larysa said. Once the school learned that she was in the military, teachers began to punitively lower Kyrylo’s grades – even if his answers were identical to his classmates.

As was the case with Valeriia and Mykhailo, classes were taught in Russian, the Ukrainian language and textbooks were swiftly eradicated, and children were made to sing the anthem of the Russia-established LPR, with many children actively involved in the Yunarmiya movement.

“Children aged 12 to 13 wear military uniforms: they have uniforms, berets, everything,” said Larysa. Kyrylo was also asked to join this movement, but her son said “no” immediately. “He is a patriot of Ukraine. I often requested on the phone, “son, don’t say anything [anti-Russian] until I take you.” He loves Ukraine so much. I brought him a blue and yellow heart with an embroidered pattern earlier, so he took it over all the borders, because that heart was given to him by his mother.” The occupation authorities wanted to remove Kyrylo from his grandparents, with his grandmother being repeatedly summoned to their “social services”.

Russia has a long track record of separating Ukrainian children from their families. A recent report from the Yale School of Public Health’s Humanitarian Research Lab noted that Russia’s programme of “forcible deportation, transfer, coerced adoption and fostering of Ukraine’s children” provides a “substantial basis” for violations of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the Rome Statute (war crimes and crimes against humanity), and the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC).

Larysa’s first attempt to get him back was in autumn 2023, but she was unsuccessful, and he had to go into hiding. Eventually he made it to Poland, after going through Russia and Belarus, landing back in Ukraine in December 2023. “At first, he had a lot of fear in his eyes after what he experienced there. At first, he lived in anticipation that they might come and take him back to the occupation,” Larysa said. He never doubted his devotion to Ukraine. “When he came here, he came home. My son said, “I don’t want to be Russian.”” Like Valeriia, he made a conscious effort to switch to Ukrainian after spending a chunk of his education forced to use Russian. However, he has no military aspirations – his mother suspects, due to his traumatic experience of war. Kyrylo now lives in western Ukraine, and just started the ninth grade.

Forced into hiding

Children who end up in the temporarily occupied territories often receive little information from parents that are desperately trying to reach them, or even the very fact that their

loved ones are trying to contact them – sending them further into despair. “The occupation authorities are doing everything they can to limit any contact with the territory controlled by Ukraine. And when the children return, they are very surprised that they were being searched for and waited for, because they did not have this information,” Nataliia Mezina, a psychologist at the NGO Ukrainian Child Rights Network, told The Reckoning Project. Her NGO is actively involved in ensuring the safe return of children from the occupied territories.

When they do manage to return, many are overwhelmed with emotion. “For children with patriotic views, meeting the Ukrainian flag is a very sensitive moment. First of all, they dream of continuing their education and rebuilding Ukraine,” she said.

Some children are also forced to go into hiding for much longer than Kyrylo did. “For children with pro-Ukrainian beliefs, the occupation is a hostile, violent environment,” she said. “I know a lot of cases when teenage boys hid in the occupation for two or three years and did not go to school … they tried to leave at any cost so as not to join the ranks of the Russian occupation army.”

Living under occupation is an intensely traumatic experience for people with pro-Ukraine beliefs, with such children feeling constantly under threat. Upon return there is a long reintegration process, “to make up not only for educational needs, but also for lost opportunities for development,” Nataliia Mezina said.

Aliide Naylor and Aleksander Palikot contributed to this report

Nataliia Sirobab is a Ukrainian journalist and researcher with The Reckoning Project.