The deadliest year yet A new investigation from Meduza and Mediazona shows Russia has lost more than 200,000 soldiers in its war against Ukraine

Earlier this summer, Russia’s Federal Statistics Service (Rosstat) stopped publishing overall mortality figures, leaving inheritance case data as the only reliable and sufficiently detailed source for estimating Russian combat deaths in Ukraine. Meduza and Mediazona have been tracking and analyzing the National Probate Registry’s data since 2023. In the six months since our last report, new entries have been added, showing that losses in the Russian Armed Forces over the past year have reached an entirely new level. In some periods, reported deaths exceeded 2,000 per week, and in the final months of 2024, they may have even approached 3,000. More recently, a new factor has emerged that affects how these figures are calculated, one we hadn’t encountered before: courts declaring missing soldiers dead. Below, we explain how this change impacts our overall mortality estimate, what we learned about combat deaths in 2024, and how many Russian troops in total might have been killed in the war by the end of summer 2025.

How we use Probate Registry data to estimate combat deaths — and why it’s the only reliable source

Since 2023, Meduza, together with our colleagues at Mediazona, has been analyzing Russia’s National Probate Registry to estimate the total number of Russian soldiers killed in the current war and track the dynamics of these losses over time.

The most reliable source of data on these losses is confirmed casualty lists that use obituaries, social media posts, and other open sources the confirm individual soldiers’ deaths. Mediazona compiles these lists together with BBC News Russian and a team of volunteers. However, they’re always incomplete, and it’s impossible to know how many fallen soldiers have not yet been included.

This is where the National Probate Registry comes in. We can use this registry as a second independent data source, allowing us to assess both the completeness of the confirmed casualty lists and Russia’s overall number of losses. That completeness level is constantly changing: it varies by year and by age cohort of the deceased. This means there’s no universal coefficient that could be applied to a confirmed list to estimate total losses.

We described our analysis of the probate registry in detail in the first article in this series, so we won’t go into the full methodology here. The analysis — especially collecting the raw registry data (tens of millions of probate cases) — is time-consuming, but the process itself is fairly straightforward.

- First, the registry includes the names of the deceased, their birth and death dates, and the dates when probate cases were opened. This makes it possible to track mortality over time by sex and age among those for whom probate proceedings were initiated. Of course, this doesn’t cover all deaths in Russia, but it accounts for a significant share (in older age groups, the registry covers up to 70 percent of all deaths). Even without any other independent data sources, this allows us to compare mortality rates among men and women. In peacetime, the ratio of probate cases for men versus women may vary somewhat, but once the war began, the number of cases involving men surged several times over — something that can only be explained by increased mortality.

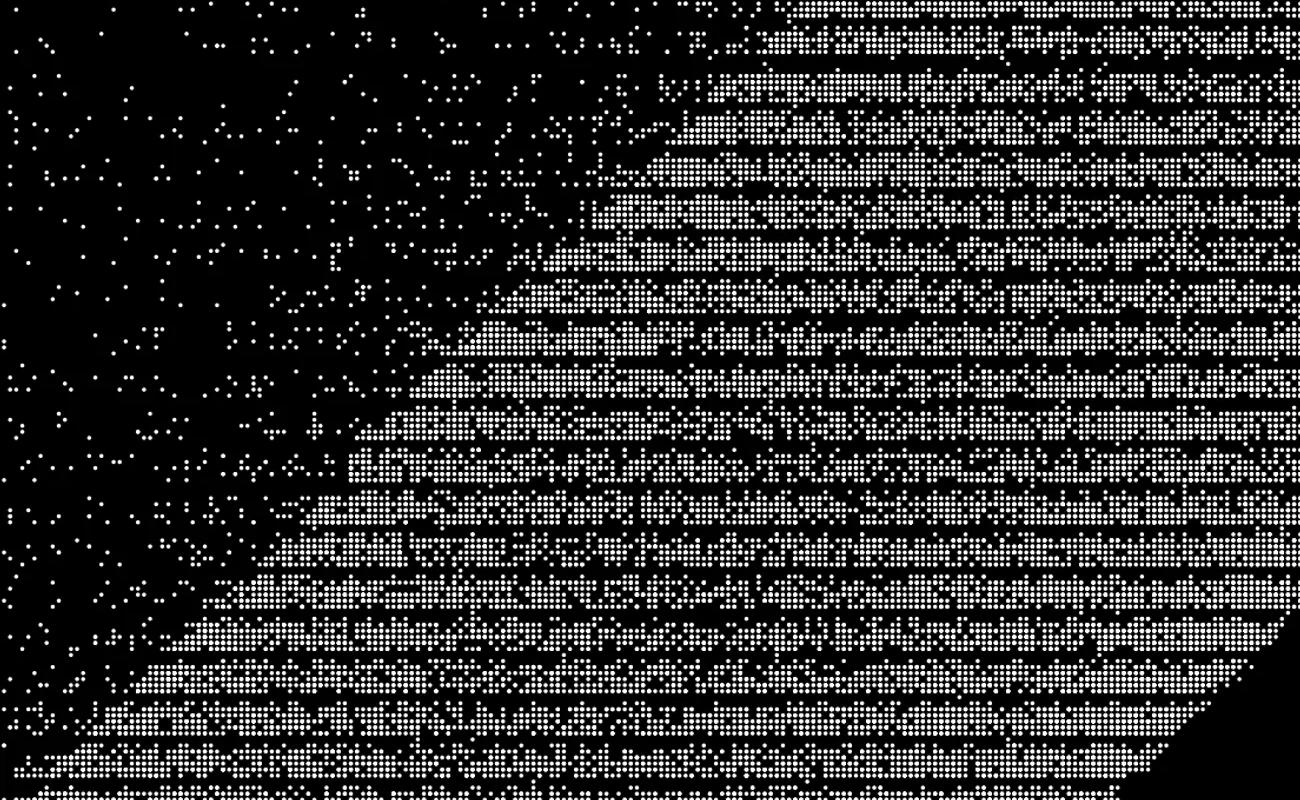

- Second, in addition to the date of death, the registry also records the issuing date of the official death certificate by the civil registry office (ZAGS). In the overwhelming majority of cases, these two dates differ by no more than a day or two. But even before the war, there were occasional cases where a significant gap existed between deaths and their registration. If we look at the pattern of these delayed registrations in the pre-war period, we see a clear seasonal trend: peaks appear during long holidays, when deaths occur but civil registry offices are closed. Gentler rises coincide with waves of COVID-19 infections, when ZAGS offices in Russia struggled to keep up with death registrations. For women, the same pattern of isolated late registrations, with small peaks on holidays, continues after the war begins — but for men, it changes dramatically. Among younger age cohorts (20–30 years old), the number of delayed registrations shot up from almost zero exactly when the full-scale invasion began in late February 2022, then dipped slightly before climbing again. Late registrations also spiked among men aged 50–55, though with a delay — not at the start of the war, but later, when convicts and “volunteers” began to be recruited and forcibly mobilized. If we use historical data on the ratio of weekly male and female deaths, we can take the current data on female mortality during the war as a baseline to predict the expected number of male deaths — and from that, calculate excess male mortality.

- All of these “traces of war” are easy to detect in the probate registry even without outside data, but combining the registry with the confirmed casualty lists gives us a full picture of losses. For example, by knowing what share of individuals in the confirmed lists also appear in the registry, we can estimate the number of deaths missing from the probate data. We can also track how the share of late registrations changes among those on the confirmed lists and use that to reconstruct the total number of war deaths in the registry. This method allows us to account for those whose deaths were registered quickly (from the lists, we know that about half are recorded within two weeks, and the rest later) without drowning in the statistical noise created by high background mortality in older age groups (45-55 years), where war deaths make up only a small fraction of overall mortality and COVID-19 or seasonality have a stronger effect on excess deaths than the war itself.

- In short, calculating war fatalities comes down to estimating the excess number of probate cases involving men — the difference between actual and unexpected figures (based on the number of cases involving women in the same age group) — and then multiplying that by a series of coefficients to convert probate cases into actual deaths.

What the new inheritance case data reveals about Russia’s army losses as of August 2025

The key insight from our latest analysis of National Probate Registry data is a sharp rise in losses, which seem to reach a new level of intensity each year. Now, six months after our previous estimate, we can confirm that this increase persisted in 2024, with losses hitting record highs. During some periods, the Russian Armed Forces lost more than 2,000 men per week, and overall, according to the National Inheritance Registry, about 93,000 Russian servicemen were killed last year — almost twice as many as in 2023, when the death toll was roughly 50,000.

The biggest challenge in producing timely estimates (aside from collecting the data itself) is the method’s built-in “blind spot”: it can’t reliably account for losses in the most recent six months. The main reason for this is that relatives have at least 180 days after a death to open a probate case, which means the latest half-year of data in the registry is always incomplete. This gap can be partially corrected by using historical probabilities of how soon probate cases are opened after a death, which helps reconstruct the picture. But this requires additional assumptions and leaves room for error, since it depends on families’ behavior around probate cases remaining consistent on average.

To address this, we’ve adopted a different approach in our latest analysis: we only use registry data once it’s complete. For the most recent six months we use a provisional estimate based on the total number of deaths in the named casualty lists, the rate at which these lists grow, and the ratio between that number and the number of people in the same cohorts on the same dates in the lists. In other words, we use a predictive model.

This model gives fairly reliable results for the overall death toll, but the week-by-week distribution can be heavily skewed — depending on how quickly Mediazona and BBC volunteers process potential entries, whether new leaks of casualty data appear, and other random factors. On top of that, the named lists also lag behind, and new fatalities don’t appear there immediately, which creates a steep drop in the charts for recent months. It’s important to remember that this drop doesn’t mean losses have decreased — it only reflects the incompleteness of the lists.

Luckily, it’s possible to gauge the relative intensity of losses using the same inheritance data. To do this, we can look at the ratio of probate cases for men versus women, which clearly shows that the increase in deaths at the end of 2024 was real. We can’t say with confidence whether losses at that point actually crossed the 3,000-per-week mark or were slightly lower (the accuracy of the calculation drops sharply in this period), but the growth is confirmed by the simple male-to-female case ratio in the registry — and it aligns with a small spike in deaths on the named lists (which are also still highly incomplete at this point).

Taking all the uncertainties of the predictive model into account, we estimate that by the end of summer 2025, the total number of Russian military personnel killed in the war was around 220,000.

A new factor in estimating losses: a surge in courts declaring missing soldiers dead

Another factor, whose effect is still hard to measure and which has only recently started influencing casualty counts, is the courts officially declaring missing soldiers dead. An analysis of civil cases filed in district and garrison courts under the category “Declaration of a citizen as missing or deceased” shows that these cases surged sharply in the second half of 2024.

By mid-2025, the number of these cases had reached 2,000 per week. In other words, courts are now “adding” to the death toll almost as much as the fighting itself.

Of course, not everyone listed as missing in court cases is a soldier killed in Ukraine. Court rulings usually redact names, which makes it impossible in most cases to match the rulings to the names of missing servicemen (which are usually found in social media groups for families searching for their lost relatives). Sometimes a court decision makes it obvious that the person was a soldier, but these cases are the exception, not the rule.

Still, the rise in missing persons by late 2024 is also visible in the National Probate Registry. One way to see it is by looking at the number of inheritance cases opened for people where a significant gap exists between the date of death and the official death certificate. Such gaps — weeks, months, or even years — did occur before the war. But when we adjust these delays to pre-war averages, a pattern emerges: it was in 2024, not right after the war began, that the number of inheritance cases involving “lost” decedents started to climb. This increase mirrors the trend in court cases.

The reason we can assume that these cases are related to the war is that the growth is observed exclusively among men. In the same chart for women, there’s no change at all — neither after the war began, nor in recent months.

It’s worth noting that the previous chart grouped cases by the date the inheritance case was opened — showing the growth in new filings and how the share of missing persons within them has increased. But these people may have died long before the case was opened. On the casualty charts we showed earlier — where cases are grouped by death date — the same individuals would appear much earlier, in the year and week when they died (or when the court ruled that they died).

Courts handle death dates in different ways, and so far we know only a few examples of how this works for missing servicemen:

- In some cases, the court relies on the decision of the missing soldier’s commanding officer — so the date of death is close to the date of last contact.

- In others, the date of death is set as the day the court ruling takes legal effect.

- Sometimes, if the ruling hasn’t yet taken effect, the official date of death can even fall in the future.

Still, a significant portion — and likely the majority — of such cases are assigned to earlier years, usually close to the actual time of death. This is clear in the next chart, which shows the same inheritance cases as before, but distributed by date of death.

It’s clear that courts tend to place these deaths (ones with a long gap between the actual death and the official death certificate) mostly “in the past.” From the standpoint of tracking loss dynamics, that’s a good thing — it introduces less distortion than if the date of death were simply set to the day the court issued its ruling. If that were the case, we’d see a surge in mortality only now, when these court decisions started coming through.

Courts may have contributed slightly to the increase in reported deaths over the past six months, but the effect seems small — otherwise, it would show up clearly in National Probate Registry data. For now, we don’t know how many missing soldiers are in the registry, whether this group can be singled out, or how the growing wave of court cases might distort the broader picture of casualty trends in the future. All of this will require fresh data that covers the past six months and a dedicated analysis.