Russia s Permanent War against Georgia

As the Biden administration works to develop its strategy to counter the Russian Federation, it is useful to reexamine traditional features of Russian foreign policy. Moscow has developed its own particular approach to strategy as the Kremlin continues its quest to be treated as a great power.[1] Russia seeks to avoid direct military confrontation with technologically superior enemies, especially Western powers. The modern Russian way of warfare is a product of this strategic thinking. Hybrid warfare is largely a continuation of Moscow’s traditional military thinking, with some innovations related to current social-political changes and modern technologies. Russia astutely uses a mixture of its national powers in different situations. The case of Georgia illustrates how Russia approaches its ways and means to uphold national ends.

Since Georgia gained its independence, the Kremlin has continued to exert pressure on Tbilisi by employing a combination of instruments of power. Along with traditional sources of power—such as using or threatening military force, supporting proxies, and creating separatist regimes as leverage against the country—Russia employs economic measures, information operations, and cyber-attacks.

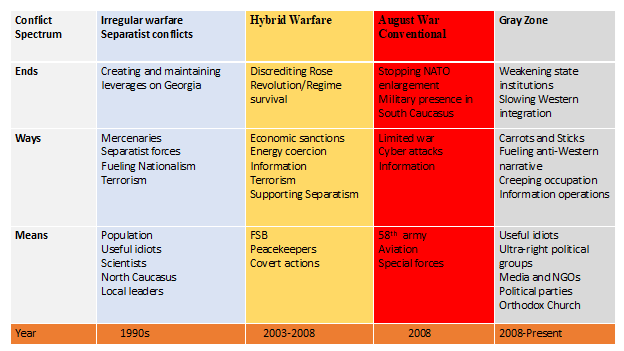

Georgia’s experience as a long-standing victim of Russian hybrid warfare illustrates that the modern Russian way of warfare is not a new phenomenon. However, modern technologies, such as cyber capabilities, the use of social networks, and electronic warfare, are new enablers for Russia to uphold its indirect strategy. Figure 1 illustrates Russia’s hybrid warfare and gray zone campaign model against Georgia from the 1990s to present.

Russia uses an assortment of powers to achieve enduring political goals. In the early 1990s, the Russian Federation fueled separatist movements in Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia.[2] In addition to providing separatists with military equipment and support, Russia waged relentless long-term information warfare. Russia effectively used propaganda and information campaigns to sow chaos and confusion within Georgia and about Georgia among its international allies. Russia’s main narrative was that “Georgians are fighting against small nations” and that Georgians were conducting a “genocide” of Abkhazian and Ossetian people. Still, the first large-scale Russian influence campaign against Georgia started after the 2003 Rose Revolution and culminated with the August 2008 war. The Kremlin realized that Color Revolutions—and Georgia’s Rose Revolution in particular—threatened its two main foreign policy objectives: stopping “encroachment” by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the post-Soviet space and maintaining a special role and influence in the former Soviet Republics.

Unlike in the Western theater, where Russia primarily relies on non-kinetic measures, the military is the most important instrument in Moscow’s hybrid warfare toolkit in the post-Soviet space. In the “near abroad,” the use of military power is understandable for several reasons: Russia has an advantage as it holds unmatched conventional capabilities, particularly when countries such as Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova do not benefit from collective security guarantees. Thus, even when Russia uses non-kinetic tools in the post-Soviet space, the effectiveness of these tools is largely backed by superior “last resort” military power. The August 2008 war was mostly a conventional one; however, Russia also used hybrid measures such as cyber-attacks and disinformation campaigns. The war served as a laboratory for lessons learned and as a trigger for military modernization for the politico-military establishment in Russia.

Since 2008, Russia has illegally occupied Abkhazia and South Ossetia, which account for 20 percent of Georgian territory.[3] The occupation gives Russia a substantial military presence in the South Caucasus. At the same time, Russia continues its “borderization process” in which it “grabs” additional lands near the occupation line in South Ossetia by moving the barbed-wire “borders” further into the undisputed Georgian territories. The situation around the occupation line is a classic example of “salami-slice tactics.” Moscow could have reinforced the administrative borderlines after the 2008 war, but instead sows discord without provoking military response.[4]

On top of military coercion, Russia continues to actively deploy information operations, diplomatic and economic pressure, and political warfare against Georgia. After achieving its initial objectives with military force, Moscow now uses non-kinetic warfare tools. Russia is Georgia’s second largest trade partner representing 11 percent of total Georgian trade in 2017-2018. Russian tourists are among the majority of foreign visitors in Georgia at any given moment. In addition to trade, the amount of remittances by Georgian citizens living in Russia has a significant share in Georgia’s economy. Therefore, this economic dependence on Russia remains one of Tbilisi’s biggest vulnerabilities and is another tool in the hands of Moscow when it needs to exert pressure.

Economic dependence is interrelated with another important tool in Russia’s hybrid warfare toolkit: anti-Western propaganda and disinformation. According to the State Security Service of Georgia, in 2018, “Disinformation was a widespread tool used by foreign forces, which with fake news and falsified facts and history, attempted to polarize the population, imposing false perceptions and fear, and influence important processes via manipulation of public opinion.” These disinformation campaigns contain messages against NATO, the European Union, and specific social groups, such as the LGBTQ community. The main message of Russian information operations is that integration with Western institutions is detrimental to the traditional Georgian identity. Russia uses a variety of sources, such as social media, state-sponsored media, non-governmental organizations, and political parties, to exploit the lack of social cohesion in Georgian society. According to a recent report from the Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies (GFSIS), “Especially vulnerable groups against Russian propaganda are mostly people, aged 50 and over because of the experience of living in the USSR; ethnic minorities, feeling isolated and marginalized; those with a lack of knowledge of the Georgian language, which makes them an easy target for Russian TV propaganda; the rural population, which sees in Russia a market for agricultural goods, but also for possible employment, and families whose members work in Russia and send remittances regularly to their relatives in Georgia.”

However, despite the leverages that Russia possesses against Georgia, its “soft” measures are ineffective because Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspiration is a widely agreed foreign policy course among key political players and wider society. Support of NATO and EU integration among the Georgian public remains steadfastly high. A December 2020 National Democratic Institute survey showed that, much like in the previous years, NATO and EU membership support stands at 80 percent on average among Georgian citizens. Additionally, this attitude has also been engrained in Georgia’s 2018 Constitution.

Russia is not in a hurry to bring Georgia under its influence more forcefully. It has already achieved its main objectives: effectively stopping Georgia’s NATO membership and establishing a military presence in the South Caucasus. Now, in order to prevent Georgia from attaining NATO membership, Russia plays a long game by using non-kinetic tools. Unfortunately, time is not on Georgia’s side since the Georgian population expects tangible results when it comes to Georgia’s integration process into Western institutions. Since NATO membership appears less realistic in the near future, Russia will continue its gradual penetration into Georgian politics to achieve its ultimate objective of changing Georgia’s chosen foreign policy course. This approach does not require significant resources and can prove effective over time.

Nevertheless, in the absence of robust security guarantees and amid Russia’s revisionist foreign policy, Georgia continues to maintain its independent foreign policy: Euro-Atlantic integration and strategic partnership with the United States. As a reliable partner, Georgia continues its participation in international security missions and remains one of the top non-NATO contributor countries in Operation Resolute Support in Afghanistan[5] and plans to continue the mission as long as Washington needs support from the Georgian Defense Forces.[6]

The views expressed in the article are the author’s own and do not reflect the policy or position of the Ministry of Defense of Georgia, the Georgian Government, or the Foreign Policy Research Institute.

[1] Carter Malkasian, A History of Modern Wars of Attrition (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002), pp. 5-6.

[2] Regarding Russia’s involvement in conflicts in Georgia, see, for example, Svante Cornell, Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus (Routledge, 2005), pp. 333-343.

[3] Georgia’s territorial integrity is unequivocally supported by the international community, including the United States. The Countering Russian Influence in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (P.L. 115-44, Title II, §253) states that the United States “does not recognize territorial changes effected by force, including the illegal invasions and occupations” of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and other territories occupied by Russia.

[4] Lyle J. Morris, Michael J. Mazarr, Jeffrey W. Hornung, Stephanie Pezard, Anika Binnendijk, and Marta Kepe, Gaining Competitive Advantage in the Gray Zone: Response Options for Coercive Aggression Below the Threshold of Major War (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019), p. 82. On the situation across the occupation line, see, Natia Seskuria, “Russia’s ‘Silent’ Occupation and Georgia’s Territorial Integrity,” RUSI, April 18, 2019.

[5] Cory Welt, “Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy” (United States Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, October 17, 2019), p. 11.

[6] Author’s interview with high-ranking Georgian official.