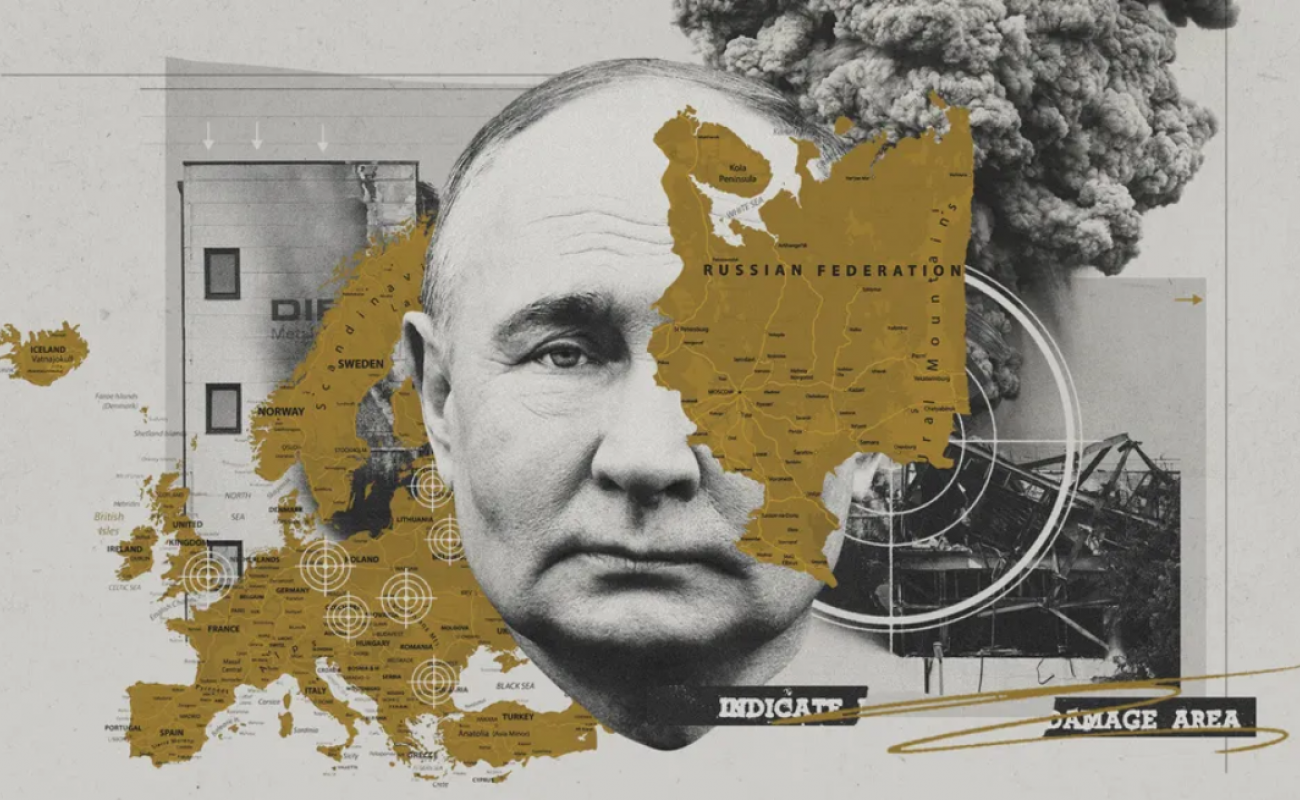

The Kremlin’s hybrid war against Europe: The alliance of spies and the mafia is the foundation of russian power

A new joint report by GLOBSEC and the International Center for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) reveals how Russia has built a state-led link between crime and terrorism, exploiting criminals to advance its hybrid war against Europe. The study places Moscow’s tactics in the context of its large-scale invasion of Ukraine and argues that hybrid operations are not a side activity but a key pillar of Russian strategy. The phenomenon mirrors previous patterns we have seen in terrorist organizations such as ISIS, which recruited criminals from Europe for violent campaigns under the guise of ideological “salvation.” Russia is said to be training socially marginalized individuals—most often those who speak Russian, live in Europe, are of post-Soviet origin, and often have criminal records—to carry out sabotage, arson, and other attacks on European soil. It is therefore emphasized that the entire process is not led by a terrorist organization, but by a state actor.

The pace of these activities accelerated after March 2022, when a wave of Russian operatives was expelled from Europe, bringing the total number of expulsions since 2018 to more than 600.

Since Moscow did not have trained operatives under diplomatic cover, it activated one of its contingency plans and began mobilizing “one-off” civilian agents to maintain its kinetic campaign as part of a hybrid warfare strategy likely designed to deter and punish EU and NATO members for their support of Ukraine, as well as to map vulnerabilities in preparation for a broader conflict. Criminals, whether as direct perpetrators or intermediaries, have enabled Moscow to adapt to reduced covert capabilities in Europe.

The study notes that since 2022, 110 kinetic incidents linked to Russia have been identified, most frequently in Poland and France. In Europe, there have been attempts to bomb critical infrastructure, plans to assassinate leading European industrialists, and even explosive devices planted on commercial aircraft. A total of 131 individuals were identified as having been involved in these incidents, at least 35 of whom had criminal records and were often recruited through prisons or organized crime groups. The typical recruit is a man in his thirties, often from a post-Soviet country, who speaks Russian and is in a precarious economic situation.

Recruitment often took place online via platforms such as Telegram, as well as through family and friend connections, creating small, resilient networks that operated locally and sometimes across borders to conceal accountability.

Financial motives were key: payments ranged from a few euros for graffiti to significant sums for attempts to attack key infrastructure.

Crucially, Russian hybrid operations are inextricably linked to illicit financing and sanctions evasion. It is emphasized that Moscow has resorted to covert financial operations to secretly transfer money across borders, pay operatives, and maintain its war economy. These channels allow the Kremlin to circumvent restrictions while integrating criminal networks more deeply into its hybrid strategy.

Alliance of spies and mafias

This strategy complements the so-called alliance of spies and mafias, which has been the foundation of Russian rule and foreign policy for years. Since the large-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, this alliance has become even more important in mitigating the economic and geopolitical consequences of Russia’s aggressive war.

The report shows the extent to which crime—whether through direct reliance on criminals to carry out attacks or through alliances between spies and mafias—forms a central pillar of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy.

The study begins with an overview of the phenomenon and traces Russia’s experience with hybrid tactics back to the 1920s. It then explores Moscow’s persistent use of crime as a tool for internal control and foreign policy, with a particular focus on the period after 2022.

The findings of this report call for a change in security priorities in Europe. Illegal trade and illicit financial flows can no longer be treated as purely economic or administrative issues. Combined with Russian direct sabotage and state terrorism, they pose a serious threat to the internal security of the EU and NATO.

Although member states are currently investing more in defense capabilities, infrastructure, and overall resilience, these resources are not necessarily directed toward internal security—the area most directly threatened by Russia. The experts involved in this project welcomed the increase in defense budgets across Europe, but stressed that part of these resources should also be directed towards strengthening internal security – strengthening the police, intelligence services, the judiciary, customs, financial institutions, and even emergency services. All these institutions are now under pressure from Russia’s kinetic campaign.

A further consequence of this campaign is the psychological pressure it exerts on societies, particularly on NATO’s eastern flank. The population is increasingly conditioned to “blame the Russians for everything,” with every industrial accident, train delay, or fire suspected of being sabotage. Although such perceptions are often inaccurate, they place an additional burden on national security systems and increase the demand for visible responses.

Finally, efforts to deter these activities are hampered by the uneven application of sanctions and border controls within the EU. If one Member State continues to issue Schengen visas to Russian citizens, another maintains cross-border trade with Belarus, and a third allows Russian trains to transit through Kaliningrad, the security of the entire Union is compromised. What once seemed like simple illegal trade now represents sanctions evasion and, in essence, an increase in the internal security gap in Europe. Russia’s approach also draws on the experience of its strategic partners. Iran and North Korea have long experience with hybrid operations through criminal intermediaries. Their formalized partnerships with Moscow open up the possibility of joint methods or complementary operations in environments where one or the other side does not have its own resources. In addition to recruiting one-off agents, Russia continues to exploit its deep ties to organized crime. Officials, intelligence services, oligarchs, and criminal networks collaborate to maintain illicit financial flows and evade sanctions.

The development of hybrid warfare

Throughout history, the nature of warfare has constantly changed in line with social changes, tactical innovations, and technological advances. About two decades ago, analysts began to recognize the emergence of a new form of warfare—hybrid warfare. The term came to refer to a mixture of conventional and irregular tactics used by non-state actors, creating complex insurgency movements in Afghanistan, Chechnya, Iraq, and Lebanon. These conflicts blurred the traditional boundaries between war and peace and between combatants and civilians.

William J. Nemeth, who coined the term in 2002, and Frank Hoffman, who popularized it in Western military circles, emphasized the importance of combining irregular methods with conventional force, complemented by new technologies. In the following years, the concept of hybrid warfare expanded significantly to include insidious tools of a political, economic, social, and informational nature in the shaping of conflict.

Of particular importance is the ability to shape and control the narrative of the conflict by influencing domestic and international audiences through information operations.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the war in Donbas have further expanded the interpretation of hybrid warfare. Countries have increasingly resorted to intermediaries, ranging from private military companies such as the Wagner Group to non-governmental organizations, political parties, or pro-Russian hacktivist groups such as Killnet or NoName057.

Today, hybrid warfare can be understood as a way in which state or non-state actors covertly use a range of political, diplomatic, economic, civil, and information instruments to achieve strategic goals. These activities are deliberately designed to remain below the threshold of open warfare or even to avoid attribution. Hybrid warfare can serve as a prelude to a large-scale conflict, as was the case with Russian operations against Ukraine prior to 2022, or as a stand-alone strategy with minimal or no conventional military intervention, as seen in current Russian operations against Western countries.

In this context, Russia’s conventional campaign in Ukraine is complemented by a parallel set of activities operating below the threshold of war, initiated by Russia or its proxies in Europe.

Since 2014, Russia has expanded the scope of hybrid warfare by involving non-state actors in the invasion of Ukraine’s Donbas region. It used “volunteers,” militias, bandits, proxies, and rebels known as “little green men,” together and then with the support of regular Russian forces.

The result was a “disorderly conflict” that allowed Moscow to officially deny involvement for some time, even though observers noted that “Ukrainian separatists in Donbas are actually a mirror of modern Russia”: a diverse group of Cossacks, tattooed bodybuilders, philosophers, mercenaries, priests, and Chechens. Crime as a tool of hybrid warfare

A distinctive feature of the Russian approach is its reliance on criminals to achieve foreign policy objectives. This aspect—crime as a means of hybrid warfare—is central to this report, with a particular focus on illicit trade as a channel through which Moscow threatens European security.

An old Soviet proverb says: “The law is like a telephone pole – you can’t jump over it, but you can go around it.” This saying still rings true today.

As one member of the Russian security forces explained: “Everyone knows we take money, and drivers give it to us. Everyone accepts it because, in reality, everyone steals a little. And no one wants to respect the law. This is the real world. We just follow this social contract.”

This attitude, combined with the chronic shortage of goods in the communist system, reinforced the dependence on the “gray economy” during the Soviet period, which, according to some estimates, accounted for as much as 20 percent of GDP. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, this trend grew into the institutionalization and normalization of corruption, where state security institutions were privatized in practice, and their “services” were available to the highest bidders.

The collapse of the Soviet Union has been described as “the most significant example of exponential growth in organized crime in the world.” Almost overnight, a chaotic struggle for wealth and survival emerged. By 1994, there were more than 500 criminal organizations in Russia, controlling approximately 40,000 businesses. In this environment, an unexpected collaboration developed between elements of the security services—including current and former KGB officials, some of whom, like Vladimir Putin, had entered politics—and the increasingly powerful criminal underworld in St. Petersburg.

In the early 2000s, the siloviki (people from the ministries of power) consolidated their control over the Russian state and positioned themselves as the “new aristocracy.” The mafia was to become “one of the branches of the Russian government” or “the criminal part of the Russian state.”

This connection enabled them to declare an end to the “criminal wars” of the 1990s, which were marked by turf wars between organized crime groups. In practice, however, the relationship between the state and organized crime has remained intact.

In accordance with a presidential decree establishing such institutions, Moscow State University (MGU) has also developed a network of “top-level” research and education centers on sanctions compliance issues.

This points to a broader pattern in which Russia effectively adopts criminal methods, including sanctions evasion, as state policy. Some recent examples:

- On July 1, 2025, a Russian citizen was sentenced to six years in prison in Narva, Estonia, for spying for the FSB and smuggling sanctioned goods across the Estonian-Russian border.

- In December 2024, the British National Security Agency uncovered a multinational crypto network that transferred funds to sanctioned Russian oligarchs and paid Russian intelligence agents. The same network also served Irish cocaine smugglers.

- The so-called “shadow fleet” – ships flying foreign flags that conceal Russian ownership but nevertheless transport Russian oil, violating international sanctions and disrupting security infrastructure in the North Sea.

These examples show how ordinary criminal activities – such as smuggling and sanctions evasion – are intertwined with covert and hybrid operations in Russia’s foreign policy arsenal.

Sanctions evasion is intertwined with hybrid operations

Following the introduction of sanctions, Russia has stepped up smuggling, which now partially fills the trade gap with the EU. According to research, illegal channels could maintain trade levels between 11 and 17 percent of pre-sanction levels, representing an annual value of between €6.5 and €10 billion in smuggled non-energy goods. Examples include:

- Russian timber entering the EU disguised as coming from Kazakhstan or Kyrgyzstan, even though these countries have very few forests;

- Plywood worth around €1.5 billion smuggled between 2022 and 2024;

- Fertilizers and oil are also disguised as coming from other countries before entering European markets;

- Kazakhstan is used as a transit point for imports of products such as electronics, microchips, and drones, which are diverted to Russia and used for military purposes;

- Parts for passenger aircraft are assembled abroad, disassembled, shipped via “intermediate destinations,” and reassembled in Russia.

Russia also exports goods from occupied parts of Ukraine, such as wheat and coal, through Asian intermediaries, while anthracite from Donbas is smuggled into Russia, taxed, and then exported to Europe as “Russian coal.”

Classic smuggling methods are being reinvented, for example, cigarettes are being smuggled into the EU in hot air balloons from Belarus.

These practices are just part of a sanctions-evasion scheme that keeps the Russian economy afloat, including traditionally controlled sectors such as tobacco. This model shows how crime is becoming a strategic pillar of the Russian economy and foreign policy.

Russia, they argue, is not the only country to use criminals as an instrument of foreign policy. China uses criminals to intimidate dissidents and control the Chinese diaspora in Europe, even organizing secret “police stations” under the guise of cultural associations; North Korea, also known as the “Soprano state,” has a state criminal apparatus (Office 39) that manages the production and trade of drugs, counterfeit goods, and other illegal activities around the world. The United States has described North Korea as a “criminal syndicate with a flag.” Iran is another example of the use of criminal organizations in hybrid operations, traditionally using its intelligence services for sabotage and assassinations abroad, which has intensified since 2014.

Since 2014, Russia has gradually expanded its hybrid operations in Europe, with notable incidents such as: explosions in the Czech Republic (2014), an attempted coup in Montenegro (2016), an attempted assassination of Sergei Skripal, a former Russian military intelligence officer (2018) in London, and the murder of a Chechen dissident in Berlin (2019).

Who are the Russian recruits for hybrid operations?

The most common nationalities are Ukrainians (26) and Russians (23), accounting for more than a third of all those identified. They are followed by Moldovans, Estonians, Bulgarians, Belarusians, Poles, British, Latvians, and Germans. Dual citizenship is common, especially among Russian-speaking minorities in Estonia. About half reside in the country where the attacks were carried out, while the other half traveled specifically to carry out the operations (e.g., Moldovans, Bulgarians, and Belarusians often travel to Central Europe). Ukrainian perpetrators are often refugees who have fled war-torn countries (2014 and 2022). Most of them had jobs in the “gray” or blue economy—construction workers, taxi drivers, etc. Several were unemployed, including Ukrainian refugees. Only 23 perpetrators expressed ideological support for the Kremlin or acted out of political/sympathetic motives. Prisons play an important role in recruitment: the cases of two Moldovan relatives in Russia and Latvia show how prisoners were contacted via Telegram and linked to Russian intelligence services. There is direct cooperation with organized crime, for example in Vienna, where the killers were paid directly by the Russian embassy. Money is the main motivator in most cases, ranging from small tasks for a few euros to larger sums, e.g., up to €10,000 for burning down an IKEA store. Initially, low-risk tasks and rewards are small, but over time, the tasks and payments increase, leading to more serious acts such as arson or sabotage. Only 58 percent of perpetrators know that they are working for Russian intelligence services, indicating that the real sponsor is unknown to many.

Some perpetrators of hybrid attacks have previously fought in Ukraine on both sides of the conflict. While on the battlefield, they establish connections with criminal networks, which later facilitate their recruitment into hybrid operations in Europe.

Online channels are key to recruitment: 55 percent of cases where the recruitment path is known involve online processes. The social network Telegram dominates, being involved in 88 percent of online recruitment. Methods vary: recruits often establish contact with pro-Kremlin individuals or are targeted as economically vulnerable persons (e.g., Ukrainian refugees seeking work). In about 44 percent of known cases, recruitment takes place in person, not just online. Family and friend ties are particularly effective because of the trust and pressure not to disappoint those close to them.

/The Geopost