Why has Russia invaded Ukraine and what does Putin want?

When Vladimir Putin shattered the peace in Europe by unleashing war on a democracy of 44 million people, his justification was that modern, Western-leaning Ukraine was a constant threat and Russia could not feel "safe, develop and exist".

But after more than a month of bombardment, thousands of deaths in ruined cities and the displacement of 10 million people inside Ukraine and beyond, the questions remain: what is his aim and is there a way out?

What was Putin's goal?

The Russian leader's initial aim was to overrun Ukraine and depose its government, ending for good its desire to join the Western defensive alliance Nato. But the invasion has become bogged down and he appears to have scaled back his ambitions.

Launching the invasion on 24 February he told the Russian people his goal was to "demilitarise and de-Nazify Ukraine", to protect people subjected to what he called eight years of bullying and genocide by Ukraine's government. "It is not our plan to occupy the Ukrainian territory. We do not intend to impose anything on anyone by force," he insisted.

This was not even a war or invasion, he claimed, merely the fiction of a "special military operation" that Russian state-controlled media are required to adopt.

The claims of Nazis and genocide in Ukraine were completely unfounded, but it was clear Russia saw this as a pivotal moment. "Russia's future and its future place in the world are at stake," said foreign intelligence chief Sergei Naryshkin.

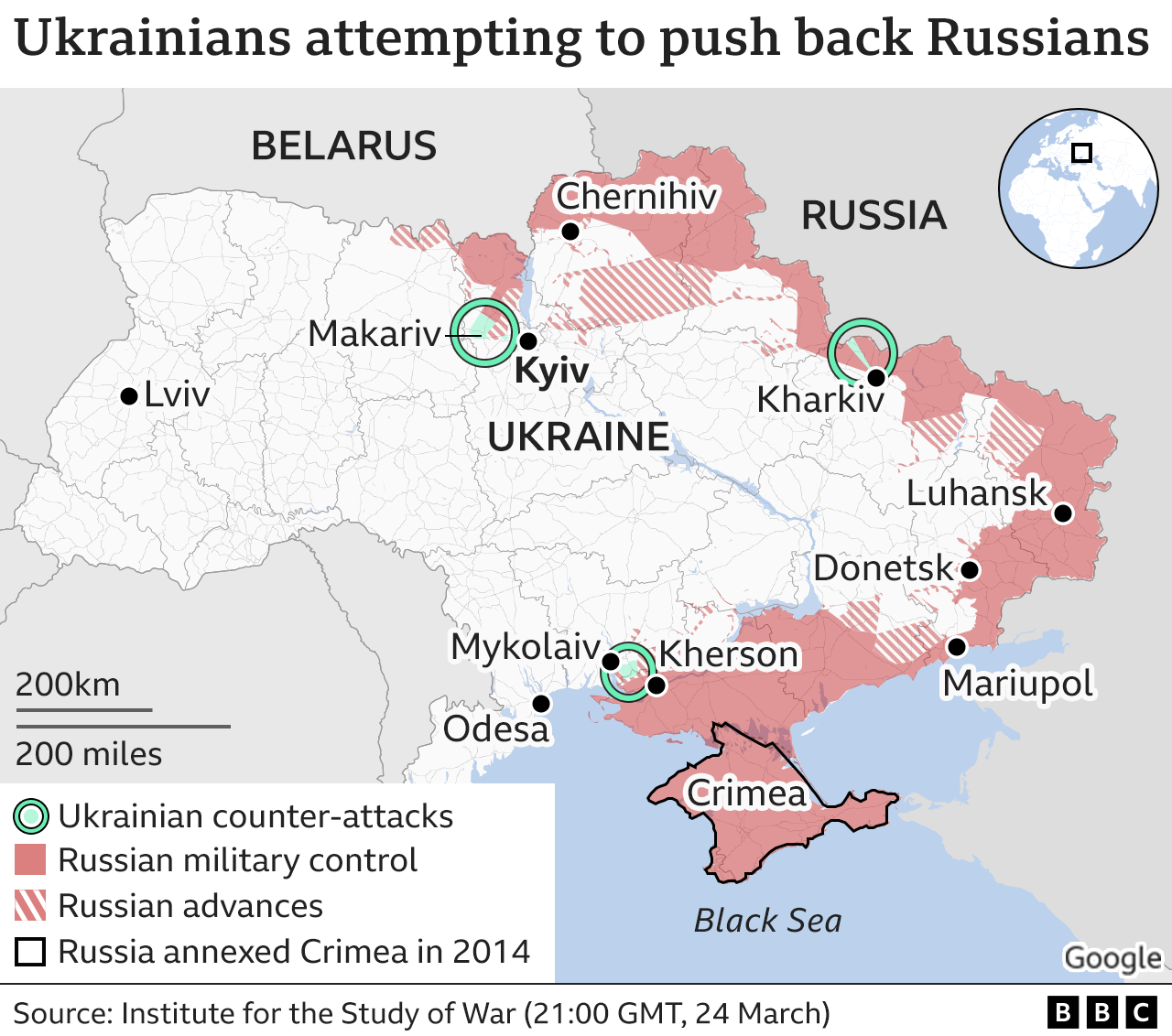

Russia's military aimed to sweep into the capital Kyiv, invading from Belarus in the north, as well as from the south and east.

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov spoke of freeing Ukraine from oppression, while Ukraine's democratically elected President Volodymyr Zelensky said "the enemy has designated me as target number one; my family is target number two".

But Ukraine's fierce resistance has caused heavy losses and, in some areas, driven Russian forces back.

Has Putin changed his aims?

Russia does appear to have lowered its ambitions, claiming it has "generally accomplished" the aims of the invasion's first phase, which it defined as considerably reducing Ukraine's combat potential.

The main goal, we are now told, is the "liberation of Donbas" - broadly referring to Ukraine's eastern regions of Luhansk and Donetsk. More than a third of this area was already seized by Russian-backed separatists in a war that began in 2014.

Russia wants all of it, as spelled out by President Putin when he recognised the whole area as belonging to two Russian puppet statelets in the lead-up to the invasion. The head of the Luhansk statelet has suggested holding a referendum on joining Russia, similar to an internationally discredited vote held in Crimea in 2014.

But Russia will also try to control Ukrainian territories along the south coast, east from Crimea to the Russian border.

And President Putin's broader demand is still about ensuring Ukraine's future neutrality.

Why Putin wants a neutral Ukraine

Since Ukraine achieved independence in 1991, as the Soviet Union collapsed, it has gradually veered towards the West - both the EU and Nato.

Russia's leader aims to reverse that, seeing the fall of the Soviet Union as the "disintegration of historical Russia". He has claimed Russians and Ukrainians are one people and denied Ukraine its long history: "Ukraine never had stable traditions of genuine statehood," he asserted.

It was his pressure on Ukraine's pro-Russian leader, Viktor Yanukovych, not to sign a deal with the European Union in 2013 that led to protests that ultimately ousted the Ukrainian president in February 2014.

Russia then seized Ukraine's southern region of Crimea and triggered a separatist rebellion in the east and a war that claimed 14,000 lives.

As he prepared to invade in February, he tore up an unfulfilled 2015 Minsk peace deal and accused Nato of threatening "our historic future as a nation", claiming without foundation that Nato countries wanted to bring war to Crimea.

But what would Russia accept from a neutral Ukraine? Russia is considering a "neutral, demilitarised" Ukraine with its own army and navy, along the lines of Austria or Sweden, which are both EU members.

"Austria was neutral, is neutral and will remain neutral in the future too," says Chancellor Karl Nehammer, even if it is part of Nato's Partnership for Peace.

But Sweden is not neutral: it is non-aligned. It has taken part in Nato exercises and Swedes have actively discussed joining in the future.

Is there a way to end this war?

Both sides have made progress in negotiations but the prospect of a meeting involving the two presidents, considered key by Kyiv to ending the "hot phase" of the war, appears some way off.

Ukraine has three core demands: a ceasefire, security guarantees and securing its sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Russian troops would have to be withdrawn from Ukrainian territory, and Kyiv will demand they return to pre-war positions.

Security guarantees would mean legally binding protection from allied countries that would actively prevent attacks and, in the event of a conflict, "take an active part on the side of Ukraine". In other words, guaranteed protection would have to be backed by parliaments in countries such as the US, UK, Turkey, Germany and France.

Ukraine has softened its stance on Nato, with President Zelensky saying that Ukrainians now understand they will not be admitted as a member: "It's a truth and it must be recognised."

The issue of Ukrainian neutrality and future security guarantees would require constitutional change, and that could be achieved in a referendum in a matter of months, says Mr Zelensky.

But Russia also wants Crimea recognised as Russian and separatist-held areas recognised as independent. This issue will not be resolved before the withdrawal of Russian troops either, but when Ukraine demands territorial integrity, that includes these Russian-held areas.

The other core issues for Russia are: disarmament of Ukraine, "de-Nazification" and having Russian recognised as a second language in Ukraine.

For President Zelensky, neither demilitarisation nor "de-Nazification" are on the table: "I simply do not get these things." Russia's claims of Nazism are unfounded and Ukraine's foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba has said bluntly: "It's crazy, sometimes not even they can explain what they are referring to."

Ukraine's president has said he is prepared to give Russian minority language status, along with the languages of other neighbouring countries, and does not see this as a major issue.

What's Putin's problem with Nato?

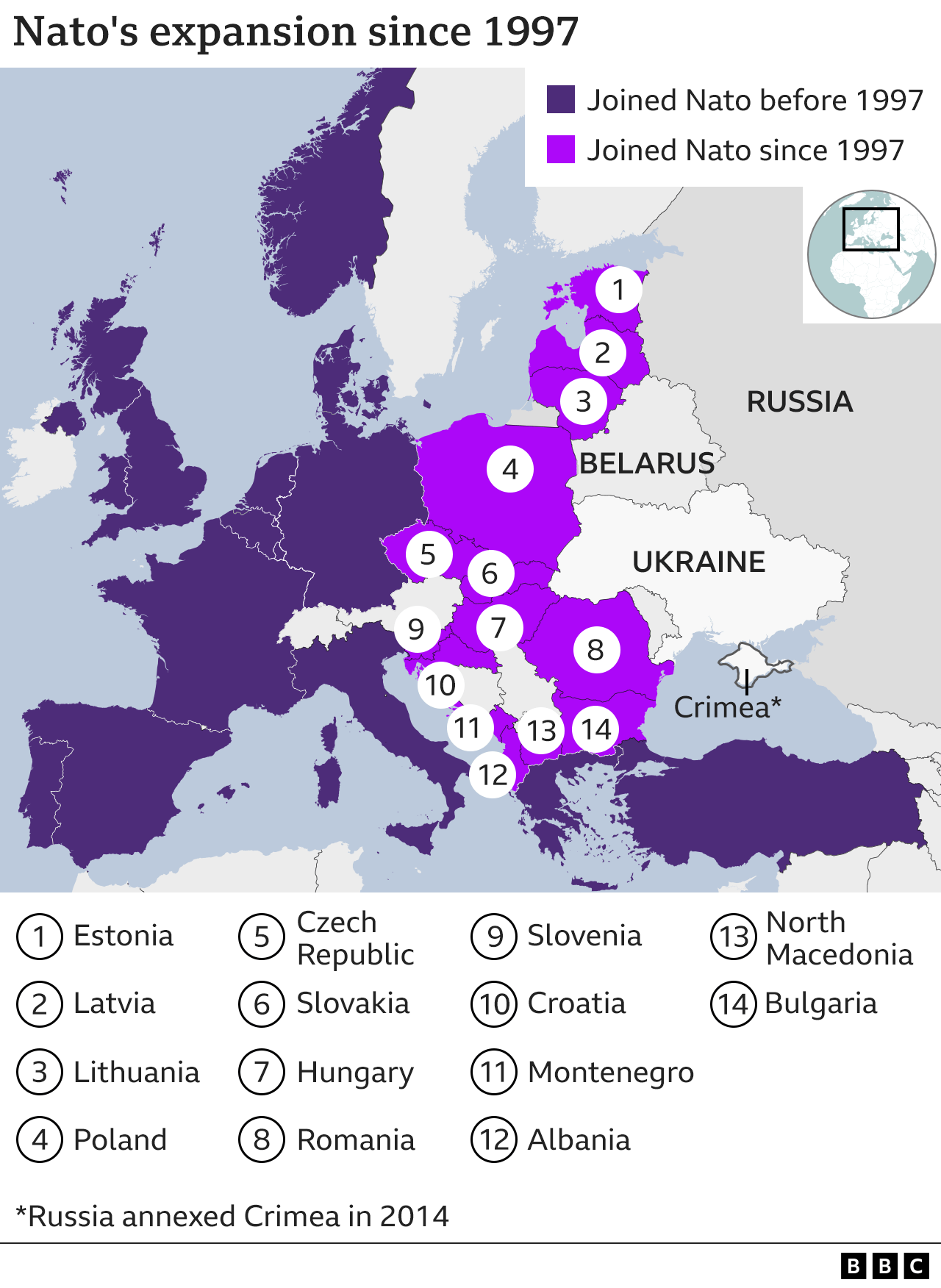

For Russia's leader the West's 30-member defensive military alliance has one aim - to split society in Russia and ultimately destroy it.

Ahead of the war, he demanded that Nato turn the clock back to 1997 and reverse its eastward expansion, removing its forces and military infrastructure from member states that joined the alliance from 1997 and not deploying "strike weapons near Russia's borders". That means Central Europe, Eastern Europe and the Baltics.

In President Putin's eyes, the West promised back in 1990 that Nato would expand "not an inch to the east", but did so anyway.

That was before the collapse of the Soviet Union, however, so the promise made to then Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev only referred to East Germany in the context of a reunified Germany. Mr Gorbachev said later that "the topic of Nato expansion was never discussed" at the time.

Does Putin have designs beyond Ukraine?

If he has, his military setbacks in Ukraine may have put paid to any wider ambitions beyond Ukraine.

After hours of conversations with Russia's authoritarian leader, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz concluded: "Putin wants to build a Russian empire... He wants to fundamentally redefine the status quo within Europe in line with his own vision. And he has no qualms about using military force to do so."

Tatiana Stanovaya of analysis firm RPolitik and the Carnegie Moscow Center fears a spiral in a new Cold War confrontation: "I have very firm feelings that we should get prepared for a new ultimatum to the West which will be more militarised and aggressive than we could have imagined."

Having witnessed Mr Putin's willingness to lay waste European cities to achieve his aims, Western leaders are now under no illusion. President Joe Biden has labelled him a war criminal and the leaders of both Germany and France see this war as a turning point in the history of Europe.

Before the war, Russia demanded all US nuclear arms be barred from beyond their national territories. The US had offered to start talks on limiting short- and medium-range missiles, as well as on a new treaty on intercontinental missiles, but there is little chance of that happening for now.